The former corporate banker discusses the challenges and rewards of leaving Wall Street for The Nature Conservancy.

Mark Tercek at Everglades National Park (Photo by Erika Nortemann/TNC)

“Buddhists have long believed and now scientists are confirming that you can train yourself to become more compassionate,” Mark Tercek tells us from his Nature Conservancy headquarters in Arlington, Va., an organization that employs more than 4,500 people worldwide. “A lot of people wiser than me who have been important in the nonprofit field somehow knew that all along.”

It might be unexpected to hear a self- described “Wall Street guy” praising the art of sitting still, but what’s really unexpected is a Goldman Sachs partner taking a 90 percent pay cut to head up an environmental nonprofit.

That’s just what Tercek, a Georgetown resident and father of four, did in 2008, a few months before the financial collapse.

“After having been a very mainstream investment banker for more than 20 years, I was thinking I should do something different. I had a notion of doing something good for society,” Tercek explains, admitting that “it wasn’t a very well-developed notion.” He planned to retire in 2005, but his boss at the time, Hank Paulsen, had a better idea: Tercek should lead Goldman Sachs’ initial environmental effort, something that was quite unusual (“even radical” he says) at that time.

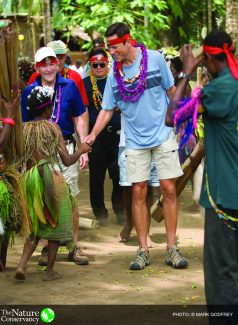

Mark Tercek greeted by native participants in singsing welcoming ceremony at Tarobi village on the Kimbe Bay Coast in West New Britain, Papua New Guinea (Photo by Mark Godfrey © 2008 The Nature Conservancy)

“Hank and I had the idea that we were going to show the world that doing the right thing environmentally was also the right thing business-wise in many cases,” Tercek says, an idea that provided useful experience for his transition to The Nature Conservancy. That came about when a headhunter called asking Tercek for a recommendation of someone to fill the role. “My idea was not anyone other than me,” he recalls, “even though my friends who knew anything about NGOs said they were never going to hire me.”

Lo and behold, they saw the value in hiring Tercek, and the “late bloomer” to environmental awareness found himself bringing an unusual perspective to The Nature Conservancy. The financially savvy businessman from Cleveland demonstrated that environmental efforts could be aligned with private sector initiatives for the common good. Plus, his big city background led to an urban youth initiative, Leaders in Environmental Action for the Future (LEAF), that aims to broaden support for nature.

“A lot of my colleagues seemed surprised that I wasn’t a very experienced fly fisherman or horse rider or regular camper and I remember thinking to myself, well those people don’t have a monopoly on the environment,” Tercek says.

LEAF is off to a great start and that is particularly important since it’s estimated that by 2050 three-quarters of the world’s people will live in cities. It also reflects his belief that the effectiveness of conservation organizations will depend on diversity to flourish.

“There’s a lot of talk about diversity right now — gender, racial, sexual orientation diversity — and that is very important for a number of reasons,” Tercek says, adding that “one of them is that diversity in general is very important.” Speaking of his professional background, he continues, “Although I’m a white American man, I brought some diversity to The Nature Conservancy…Mixing things up is very good for probably all organizations, certainly for us.”

But it wasn’t smooth sailing at first. Tercek is candid as he recalls the stress he felt in the beginning as a first-time CEO, and how an executive coach and Buddhist meditation helped him change his mindset.

“I was doing a decent job broadly but I could tell on the interpersonal front things weren’t perfect, both with my colleagues and with the board.Then a friend of mine, well- known executive coach Marshall Goldsmith, volunteered to give me pro bono executive training and, after interviewing the people I worked closely with, let me know that I was being a real jerk. I wasn’t listening well. I was too negative. If I was having a bad day I let people know I was having a bad day. If I was bored in a meeting I let people know I was bored and he helped me understand that as a CEO you really can’t do that. Everybody’s looking at you.”

Tercek found that reforming these bad habits was more difficult than anticipated but somewhere in the process, he discovered meditation. That’s when everything became easier.

Buddhist meditation practices were “my big a-ha moment,” Tercek says, “that this notion of caring about others more than yourself is the way to be happy. And I realized that that’s what the people who work for The Nature Conservancy or support us have discovered. That’s why they’re so happy. They’re not thinking about themselves all day, they’re thinking about how to make the world a better place. It sounds obvious when I say it, but it was only through Buddhist meditation that I became aware of that.”

Tercek’s passion about the subject has led him to speak at an upcoming mindfulness summit. He and his wife Amy support Minds Incorporated, a local group that works to instill the practice in schools across Washington.

Mark Tercek during a birding tour of the rainforest above Kimbe Bay in Papua New Guinea (Photo by Mark Godfrey © 2008 The Nature Conservancy)

And at work, he’s been thriving. He travels three to four days a week, overseeing projects that include community conservation work in northern Kenya, the Great Bear Rainforest in northern British Columbia, the Virginia Coastal Reserve and, one of his favorites, Montana, where The Nature Conservancy has permanently protected almost 500,000 pristine acres. This was accomplished by implementing his practice of impact capital — raising money from investors to lever up donor equity while promising them a full return, some of it financial and some through impact.

He’s also doing this in Washington to solve the problems of storm water runoff. The Nature Conservancy has raised funds from an institutional investor for green infrastructure within the city (green roofs, parks, quasi wetlands) to capture storm water, reducing the impact on the environment and also beautifying areas that could use that kind of investment.

Not surprisingly, Tercek thinks climate change is now the biggest man-made threat to the environment.There are reasons to be encouraged, he says, ratting off a few: the Paris convention, progress in China, the “belated but good progress” the U.S. is finally making, the fact that solar and wind costs are plummeting. What’s discouraging, he says, is the political divide.

“We [The Nature Conservancy] actually think environmental progress is important for economic progress too, and we think there are market-friendly, economically friendly ways to address climate change.We regret that right now on Capitol Hill it seems to be a partisan issue, so we’re going to do everything we can as a nonpartisan organization to reduce the divide and find pragmatic common ground so that we can make more rapid progress.”

He’s started in the U.S. with what he calls the 50-state initiative. A board of trustees in every state (equal parts Democrat, Republican and Independent) shares the concern for climate change and a dedication to be a voice for pragmatic, market-friendly ways to deal with it.

With all these challenges, the biggest thing Tercek has learned on the job might surprise you.

“I came to The Nature Conservancy thinking that market-driven principles and a businesslike approach would be the answer to everything. And I was partly right,” he says. “We’re utilizing those strategies very effectively and it’s allowing us to get more and more done, but what I’ve learned is that’s insufficient.To really succeed in this kind of work you have to appeal not just to people’s minds but also to their hearts.”

While attending Nature Conservancy events, Tercek noticed that “the oldest supporters, some in their late 80s, often seemed like the youngest, most curious, upbeat people in the room because they’ve found the secret to the fountain of youth: engage in important causes with your heart and mind and you not only make the world a better place, you make yourself a happier person.”

This story appeared in the April 2016 issue of Washington Life.