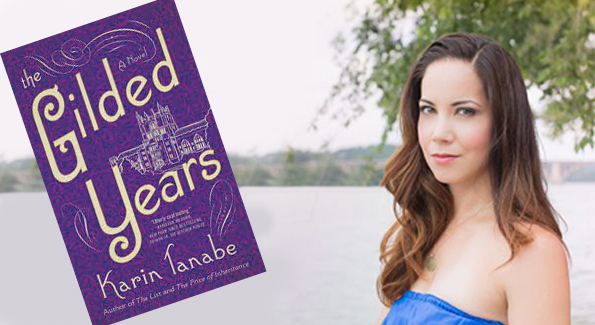

Images courtesy of Karin Tanabe/Photo Illustration by Washington Life

Karin Tanabe’s Vassar-set novel, The Gilded Years, brings a little-known historical figure to life.

If you’re looking for a book to throw into your beach bag this summer, look no further than Karin Tanabe’s The Gilded Years. Karin’s third novel is based on the true story of Anita Hemmings, the first African American woman to attend Vassar, in the class of 1897, by passing as white.

It’s an engrossing read, populated with fascinating characters. Anita herself is bright and endearing, and her privileged, pretentious roommate, Lottie, is larger than life in all the best ways that a character in a novel can be. Washington Life was lucky to be able to chat with Karin, who was the magazine’s Managing Editor from 2008 to 2010 before moving on to Politico and then to her first novel, The List, inspired by her experience at the D.C. institution.

Anita Hemmings (Photo courtesy of the Vassar College Archives)

WL: How did the idea for The Gilded Years come about?

I went to Vassar College – I was reading a stack of old alumni magazines, and I came across one from 2001. Anita Hemmings was on the cover, and she’s such a gorgeous girl that it compelled me to open it. I read about how she was the first African American student at Vassar but passed as white until the end of her senior year, when her roommate outed her true race with the help of a private detective, and essentially ruined her life. So I thought this was a really interesting story, and I was surprised that it wasn’t better known – I, as an alumna, didn’t even know about it. I thought it would make a great historical fiction book. It would make a great non-fiction book too but as a fiction writer, I thought it would be more fun if I could take some liberties with it.

WL: Why do you think Anita Hemmings’ story isn’t better known?

I think the stories of minority women, for one, don’t get enough attention. Vassar is a small school, but even if she was from a bigger school, the interest hasn’t been there. I think our conversations about race have gotten increasingly impassioned lately, so there is more of an interest in her story now, which is great. I’m very glad.

WL: What are some of the challenges of creating fiction based on a real person, and how did you overcome those challenges?

It’s kind of terrifying, even if they’re dead, because they have relatives. For me it was especially that Anita Hemmings was such a remarkable person, and she didn’t want to be in the limelight, so I grappled with that as I wrote about it. And I wanted to do her justice, because she endured so much and she was such a smart and remarkable woman. If people hate your made-up characters, it’s one thing, but if people hate this character who was actually alive and pretty remarkable, then you clearly did something wrong. I didn’t want to have that happen.

WL: So how did you make sure that didn’t happen?

I tried to only fictionalise things that I couldn’t find out. I tried to stay very true to her own story and I did get in touch with her family and gave them the opportunity to correct me if I was wrong.

WL: Did you ever feel a sense of trepidation at depicting a community – the African-American community – that you’re not part of?

I feel strongly about writing characters who are not white. In every one of my books I’ve had characters who aren’t white. In my first book [The List, Washington Square Press, 2013] the love interest was Mexican American. It’s something that I’ve really paid attention to, so I wanted to be very sensitive in my descriptions and my portrayal of Anita Hemmings. I think it’s important for anyone of any race to write characters who aren’t white, because literature is mostly written by white people, read by white people, reviewed by white people, and it’s got to change. It’s a huge problem in children’s literature, and it’s certainly a problem in [adult] fiction too. So I think the more minority characters we can create, the better.

WL: This is your third novel. What have you learned since your first, and how has your writing changed over time?

This is a different book for me. It’s my first historical fiction book and it’s my first book written in the third person, so that was a huge departure in and of itself. But I think I’m definitely a better writer now. I understand more how to plot a book, how to do character development, how to show rather than tell, and that just comes with practice. I was intimidated when I started, because it felt so different, and it took me longer to write this book. But I think it’s my best one yet.

WL: Can you talk a bit about your research? How did you go about that?

The thing about people who aren’t famous, especially the people who have long been deceased, is that so little exists. You have to take what you can get and build from it. I spent a lot of time looking at census records, slave records, phone books, death certificates, and then everything that had to do with Vassar. Her yearbooks, any mention of her in the school newspapers, anything that had to do with her daughter, who went to Vassar. You can probably put what I found on three or four pieces of paper – besides the newspaper articles that came out about her, and even that would only get to 20 pages – and somehow you have to turn that into 400 pages. So it takes a lot of imagination.

WL: How was your time at Vassar?

I love Vassar. I feel passionately about the school. It’s certainly a school that’s changed a lot since Anita’s time. They were the last Seven Sisters school to integrate. They didn’t accept African Americans till 1940 and that’s certainly a stain on their history, but I think they’ve come to terms with that and it’s certainly now a very open and inclusive school. I love the school, and I think Anita loved the school too – she sent her own daughter there. Obviously it had its faults when she was there, but I think she still felt positively about them because they did let her graduate from the school.

WL: When you write, you tend to get very attached to characters and to the world that you create. So would you ever go back and revisit this world – maybe write a sequel?

There isn’t a book that I’ve wanted to write a sequel to more than this one. Anita Hemmings’ daughter was so fascinating. She went to Vassar and she graduated in 1947. She was on Broadway and she was in Oklahoma!. There is nothing whiter on earth than being in Oklahoma!. She passed as white for her whole life. And there’s another girl in the book named Bessie Baker who went to Wellesley and she had fascinating children as well. So I’d love to write a sequel set in the 1920s about the next generation.

WL: Is that going to be your next book or do you have another one in the pipeline?

You’ve got to have a book really take off to have them let you write a sequel, so hopefully that will happen. But my fourth book is a love story, a World War II love story. It’s way more about love than war, thank goodness. It is set mostly in Asia in the 1940s. I tell everybody my fifth book is going to be about a cocktail party because these are sort of heavy, and I need a good time.