|

T

he Phillips Collection – the art collection that so many Washingtonians describe as their favorite – was born out of equal parts of love and loss. The Great Influenza Epidemic of 1918 killed 100 million people around the world, including the beloved

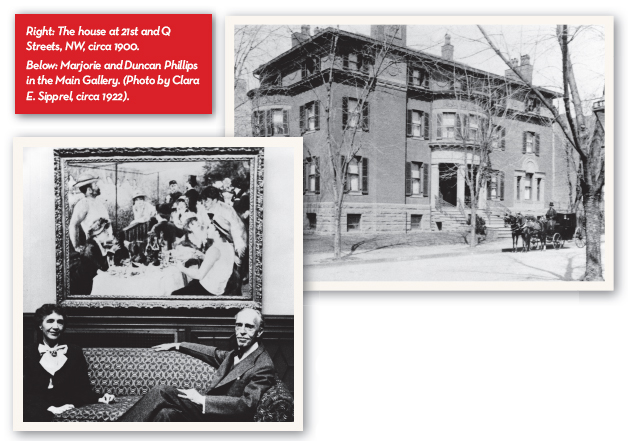

brother of Duncan Phillips. James Phillips’ death occurred only a year after Duncan’s father died, and the weight of these tragedies plunged Duncan Phillips into a state of despair. His love of art, by his own description, saved him. Heirs to the Pittsburgh Jones and Laughlin steel fortune, the Phillips brothers grew up in the family mansion in Dupont Circle at 1600 21st St. NW. They were so close that when James finished high school, he waited for two years for his younger brother to graduate, so they could go to college together. The brothers both became enamored with art at Yale, where Duncan aspired to be an art critic. But the

man who went on to open the first modern art museum in America wasn’t always inclined toward the latest artistic trends. When Duncan attended the history-making New York Armory show of 1913, he called the exhibit of French Impressionist paintings “stupefying in its vulgarity.” He wrote that Cézanne was an “unbalanced fanatic,” Gauguin was “half savage,” the Cubists were ridiculous, and Matisse was “poisonous.” There is a saying that only unthinking people never change their minds, and Duncan Phillips changed his point of view radically. He soon fell in love with the very art works he had once derided. When James died, Duncan was able to recover from his depression through his vision of a great art collection that he would assemble to honor both the memory of his father and his art-loving brother. He developed a passion, if not an obsession, for modern art, and ended up

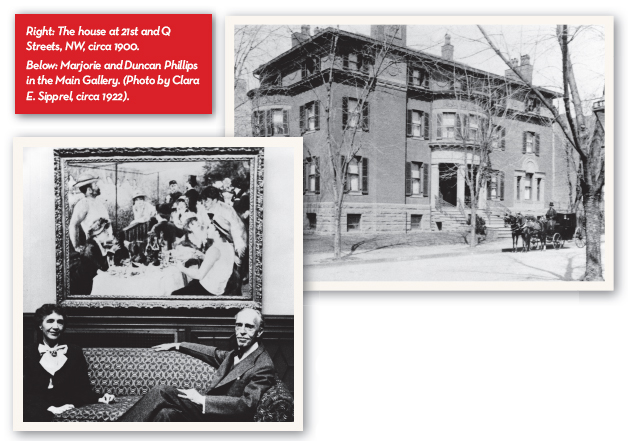

spending the rest of his life creating a monument to the artists he came to cherish. In 1920, as fate would have it, he met Marjorie Acker, a painter who had as good an eye for art

|

as he did. They got married and moved into the Phillips family mansion, where they turned two of the rooms into gallery spaces for public viewing. They stayed in the house for many years, until the growing collection – and the space it required – crowded them out. The Phillips Collection gained world renown after Duncan purchased Renoir’s masterpiece, “Luncheon of the Boating Party,”

in 1923. He paid $125,000 for it, which was an enormous price at that time – his entire year’s budget for buying paintings. The story of rival collector Dr. Albert Barnes’ reaction to Duncan’s acquisition is a favorite of Phillips’ fans. Barnes, a hugely wealthy drug inventor and art patron who bought French Impressionist paintings by the carload, teased Phillips, saying, “That’s the only Renoir you’ve got, isn’t it?” Phillips replied, “It’s the only one I need.” Marjorie and Duncan Phillips encouraged and

patronized dozens of American artists, including Georgia O’Keefe, Milton Avery, Arthur Dove and Washington artists Gene Davis and Kenneth Noland. Duncan Phillips used to stroll through the gallery and talk to people about the paintings, which he moved from room to room, mixing up styles and periods, so the pictures could, as he said, “talk to each other.” He wanted the viewer to see how artists from different periods and places influenced one another; how they passed ideas along; and how they reshaped their use of

color and light. This unorthodox arrangement of artwork grew out of Phillips’ desire for people “to see beautifully, as artists see.” Colors appear even more vivid, the thoughts and feelings expressed in the art more penetrating and resonant. Today, because of the generosity of contemporary art collectors, Phillips’ vision – and his collection – is alive and growing. New pictures and paintings are added each year. While the pictures are sent out periodically to exhibitions around the world, they always come

home again, where they move from room to room, talking to each other. The gallery is the place where James Phillips died so many years ago, and this jewel of an art collection is the phoenix that rose from the ashes of grief to beome a gift of joy and transcendence, just as Duncan Phillips meant it to be.

|