Martin Puryear, “Vessel,” 1997-2002, eastern white pine, mesh and tar, courtesy of the artist. (c) Martin Puryear, courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery.

New exhibition of D.C.-born artist showcases iterative genius in first comprehensive interdimensional dialogue.

The first chapter of “Martin Puryear: Multiple Dimensions” — a first-of-its kind Smithsonian American Art Museum show presenting the D.C.-born artist’s sculpture and works on paper in comprehensive dialogue — charts a steady course of change within shape.

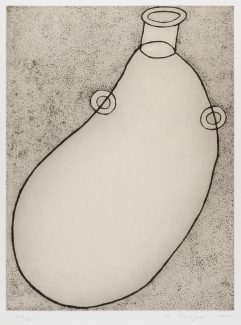

The forms are sequential, escalating from an abstracted “Jug” with eye-like handles and a distinctly spinal stem to a head-shaped form of the jug inverted, represented in a careful wireframe of topographic contours and conic crosscuttings, its stem now truly jugular.

Martin Puryear, “Jug,” 2001, hard and soft ground etching with drypoint on Japanese paper, laid down on paper (chine collé), Smithsonian American Art Museum. (c) 2001 Paulson Bott Press.

Martin Puryear, “Face Down,” 2008, white bronze, courtesy of the artist. (c) Martin Puryear, courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery. Photography by Jamie Stukenberg, Professional Graphics.

The head is next colored in, its framework hidden beneath deep, dark conté crayon, then its edges blurred as Puryear tests the form’s resolve. He ultimately frizzes it out entirely though erratic yet calculated medium manipulation, with brushes and fingerprints lovingly kneading the form through two dimensions.

Satisfied with its capacity for permanence, then, Puryear adds a third. Roseate wood grain mimics the contouring isopleths, while a dark wood sculpture emulates the crayon. A silvery bronze transmutes it, as the “Jug” was, to the titular “Face Down” position, adding hair follicles and more pronounced ears.

Then he explodes it, making an enormous face-down sculpture of interlocking wood and showing us the deepest iteration of all: the inner ideas, slyly represented by a thoughtful ampersand and a spherical period, solitary, literally punctual and mysteriously pensive.

But of course it’s not just a head anymore, either. As its title and form slowly reveal, “Vessel” is also boat-like, with hull struts of wood plunging into the gallery carpet as if it were a waterline. The neck becomes a figurehead, and the ampersand’s tar-and-mesh coating is now distinctly maritime oakum caulk.

The form will repeat, as will the idea of transmutation and evolution, within the show, which was organized by the Art Institute of Chicago and opened May 27. The museum excels by showing this iterative process simply at first, allowing us to very literally watch it progress before expanding the concept.

The mark to Puryear and local curators, then, is that the iterations do not follow each other chronologically. They build in form on individual papers before us, but in Puryear’s mind they exist as slices in his genius simultaneously, just artificially separated for our own understanding.

“I think it would be impossible to organize this chronologically,” SAAM Sculpture Curator Karen Lemmey said at a press preview May 26. “He didn’t work in a linear manner,” she said, preferring to use the term “spiral,” which is uniquely apt from an artist for whom arches, loops and curves are core.

“You’ll see in every episode, … if you look at the dates,” Lemmey said, “that … we’re passing through time or going backwards and forwards across time, watching how this form takes shape in both works on paper as well as sculpture.”

Our lucky journey, then, it to witness firsthand that genius’s development, from charcoal memories of huts, plants and people in Sierra Leone past printmaking school in Sweden through to his works of record across the decades.

“The more you look,” Lemmey said, “the more you can find these threads that you can braid into interpretation.”

Martin Puryear, maquette for “Big Bling,” 2014, birch, plywood, maple and 22k gold leaf, courtesy of the artist. (c) Martin Puryear, courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery. Photographed by Jamie Stukenberg, Professional Graphics.

In some works there seems to be an affinity for piercing, melded with the drawing-tested bent-over form to create a back-broken laborer shackled ‘round the neck, a braying bull pierced through its septum or myriad other interpretations.

The massive golden ring of “Big Bling” — a maquette for a full sculpture unveiled recently in New York City — is a clear nod to such jewelry.

The idea of bodily adornment is visible in a looping sapling sculpture whose ends are capped with joined wooden heads that hark back to the checks of golden bangle bracelets or nose rings.

The bent-over form of “Big Bling” and “Shackled” repeats many times over on paper and in elephant-like sculptures, and the negative space at the two works’ centers is undeniably ear-shaped, subconsciously reinforcing the piercing theme.

Martin Puryear, maquette for “Bearing Witness,” 1994, pine, courtesy of the artist. (c) Martin Puryear, courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery. Photography by Jamie Stukenberg, Professional Graphics

That negative ear space is rendered positive in the chronologically earlier “Bearing Witness,” a public sculpture in Federal Triangle whose maquette is on view.

“That positive form finds its way in occupying a negative form in the sculpture,” Lemmey said, gesturing to “Schackled.” “There are other instances where … the negative form you see here became a positive sculpture.”

His past is woven into the works immensely. Aside from Sierra Leone, where he served in the Peace Corps, Puryear makes similar homage to Shinto architecture observed while on a Guggenheim fellowship to Japan and to the careful European printmaking tradition he learned at Sweden’s Royal Academy. His sapling work draws directly from time spent at the Yaddo artists’ colony, and this critic found desperately intriguing comparisons to the Constructivist movement and Vladimir Tatlin.

Most visible in an untitled 2001 work that resembles strongly Tatlin’s best-known work, the connection was dismissed by Lemmey when asked, in favor of a convergent evolution of sorts — similar conditions driven by similar histories birthing, unknowingly, an eerily similar expression. An expression intriguing in its nod to the engineering behind and within a work and the concept of an abstract, formless idea made entirely physical in both two and tree dimensions.

Lemmey said Puryear likely knows of Tatlin, but dismissed him as an influence, instead embracing a National Gallery curator’s link between a similar Puryear in their “Three Centuries…” show and the work of John James Audubon (an artist referenced in the show’s AIC-written catalog).

But Lemmey, Puryear and the works themselves leave open the door of interpretation.

“He’s … very reticent of explaining things,” Lemmey said, with titling that “opens up rather than shuts down the discourse.”

“I trust people’s eyes,” she quoted Puryear as saying. “I trust people’s imagination.”

“I trust my work,” he says, “to declare itself to the world.”

“Martin Puryear: Multiple Dimensions” runs through Sept. 5 at the Smithsonian American Art Museum.