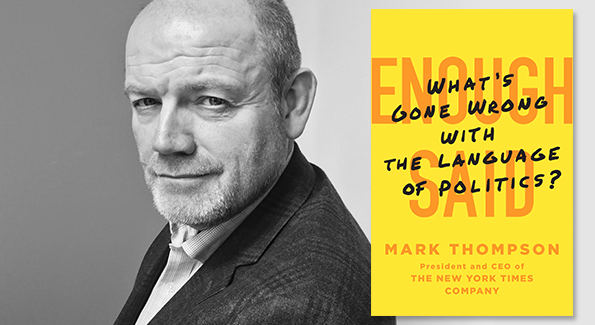

New York Times Company CEO Mark Thompson unpacks political rhetoric in ‘Enough Said.’

Photo of Mark Thompson by Kathy Ryan

“Public language matters.” So Mark Thompson begins his insightful and ever-relevant new book, “Enough Said: What’s Gone Wrong With the Language of Politics?” (St. Martin’s Press). The former BBC director general and current New York Times Co. CEO draws from his decades in media to explore how what he sees as a “crisis of trust” in politics across the Western world is, at its core, a crisis of language.

Washington Life: Obviously this book is very timely.

When you started writing it, did you have any idea about Brexit or Donald Trump?

Mark Thompson: I didn’t. I started it in 2012 when I became interested in the way the healthcare debates in America and in the U.

K. were developing. My book begins with Sarah Palin in the summer of 2009 when she coins the phrase “death panels” to talk about one aspect of Obamacare. She tweeted it out and within a few weeks most Americans had heard the phrase and many believed that it must actually be in the legislation. Trump represents an extraordinary development of that kind of style – that very high impact, very tweetable, very compressed use of language, and it carried him from being a rank outsider to becoming one of the central figures, as we speak, in American politics. It’s incredible. And a lot of it’s about language. What’s fascinated me about this election cycle is about how much, on both sides, it’s about a critique of language more than a critique of policies.

WL: As a longtime TV producer, how did you see the language of politics change with the rise of the 24/7 news cycle?

MT: First, it squeezes thinking time, so it’s harder for journalists and editors to really think these things through. The second thing is you get these very rapid feedback loops. We can see it right now in the election campaign because everyone involved is very anxious to keep up and to reflect exactly what’s going on. These real time blogging sites mean that people react in seconds. The kind of ways in which stories would develop and people would react, which would perhaps have taken days or even weeks once, now happen in minutes and hours, and it can sometimes lead to really exaggerated responses to stories. In terms of the way language is changing, I think the 24/7 cycle acts as a really powerful accelerant.

WL: Does the rise of digital media have a lot to do with that?

MT: Donald Trump’s intuitive use of Twitter in particular is very striking. It’s got incredible freshness and memorability, and one of the ways he made his mark is he seemed to be filling the digital space with his views, his comments, his reactions, his rebuttals 24/7.

WL: What do you think can be done at this point to change this trend in the language of politics?

MT: We all need to take a deep breath. Politicians need to stop talking down their profession.

Doctors don’t attack the profession of medicine when they talk in public. They don’t say, “It’s horrible being a doctor, all doctors are liars and cheats.” Most politicians are not bad people, most are basically very public spirited people, so I think politicians need to give each other more space, treat each other with a little more respect. The parliamentary debate setup is there for a reason; those conventions are broken down and need to be reestablished. The media need to give the politicians more space. But the biggest thing is to make sure that children and young people are given the chance to develop the critical faculties that one needs to unpack and understand what politicians are saying and how the media works. What I worry about is if we lose the idea of an electorate and a citizenry who can actually make informed decisions because then, if you’re not careful, you end up with a democracy based on surges of emotion and instinct, and I think history suggests that that’s dangerous.

WL: You write that the media needs to reject perspectivism, the notion that everything is a point of view and that truth is a meaningless concept. How do you see that playing out in this election?

MT: It’s been very difficult. There’s been so much mud flying and so many allegations and all the rest of it. I find it hard to be fair in an election period because we tend in elections to widely report what candidates claim, but over the course of this election, The New York Times and other newspapers have become more confident about saying, when it’s appropriate, that something isn’t true. For example, Donald Trump’s claim that he had been against the Iraq war simply doesn’t accord with the record of the time when he said he was in favor of the war. I think we’ve gotten better at saying facts are facts. Once you start arguing in a postmodernist way that everything is opinion, that there’s no such thing as a fact, journalism begins to break down. We need to be thoughtful about facts and sophisticated about the reality that many facts are in fact mediated and adjusted by opinion. We need to stand up for free speech and the right of the press to report what’s going on and that was very neatly expressed in the response written by our lawyer David McCraw to Mr. Trump’s lawyers, about what the First Amendment actually means.

WL: You write about Margaret Thatcher’s public persona and how she struggled to connect with people, and a lot of people say Hillary Clinton is too serious or humorless and they just find her unlikable. Do you see any similarities there and do you think gender has anything to do with that?

MT: It seems there’s something else going on, which is that it’s very tough to be the first. It’s very tough to be the first black president. It’s very tough to be the first completely serious female candidate to be president of the United States. And the fact that the public is unused to the idea of a black president, of a female president, means that unreasonable scrutiny, prejudices and possibly exaggerated expectations of what’s possible all make life more complicated for the first person to do that. Theresa May is still subjected to some sexist comments and some scrutiny of what she wears and her family life, which would not be true of a male politician, but for the most part she is regarded as another British prime minister. The fact that she’s a woman has been far less talked about and discussed in the U.K. than when Thatcher was. I think it’s just like in the workplace. When it’s routine for women to reach the very highest offices in the land, to become chief executives, to become vice president and president, when that’s routine…life will be easier. Unreasonable scrutiny and yes, prejudice, are part of what’s going on, and with Hillary, I’ve been very struck by the difference between her persona when you talk to her one-on-one and her public persona.

WL: How is Hillary different in person than she appears in public?

MT: I certainly have the sense that there’s a guardedness and an armor plating to her public persona, which may simply be the result of so many decades in the public eye and often under attack. I would hope that if she becomes president some of the Hillary Clinton I saw – more mischievous, more relaxed, would come forward. That’s probably true of all public politicians. It’s a pretty punishing environment. The ideological divide has become much more sharp, politics much more personal. Allegations are far more common than they used to be. It’s become a world of rage and paranoia on the internet.

That hasn’t helped. The relationship [between politicians and the media] feels very frayed at the moment. And although I always think the media should hold politicians to account, I also think [it’s important to] create some space for politicians to present themselves to the public and set out their ideas in a way which is not always filled with challenge because, if you’re not careful, you will end up with politicians who are always speaking behind barricades so you’ll never really get to know them.

This interview has been edited and condensed.