Exhibition in Paris mixes art and history in exploring discrimination

By Michele Langevine Leiby

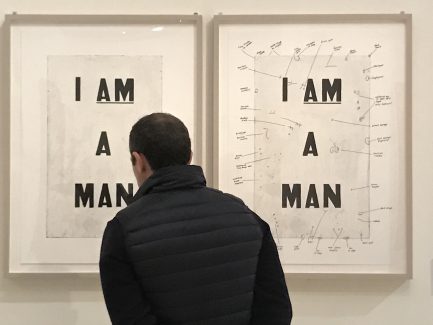

At the Musée du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac (Photo by Michele Langevine Leiby)

France loves its romanticized version of black America – the Paris of the last century that drew such celebrated exiles as Billie Holiday, Josephine Baker and James Baldwin. Their names still summon in the French imagination scenes of smoky jazz clubs and romantic cafes.

But now, finally, France may be coming to a reckoning with the reality behind the black exile experience: those luminaries and many others left the United States because of raw racism. There was nothing romantic about it for them.

That is the lesson of a timely and fascinating new art exhibition in Paris, “The Color Line: African-American Artists and Segregation” It explores for the first time in France — and perhaps all of Europe — the great divide between white and black that has governed the American experience from slavery to the “Black Lives Matter” movement of today. The exhibition is staged by the Musée du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac, a relatively new (10 years old) museum known for its emphasis on non-Western cultures and created by the former president.

It should provide the French a solid grounding in the antecedents for the modern U.S. black experience. For visiting Washingtonians, it could be taken in as an informative adjunct to the sweeping collection at the Smithsonian’s recently opened National Museum of African American History and Culture.

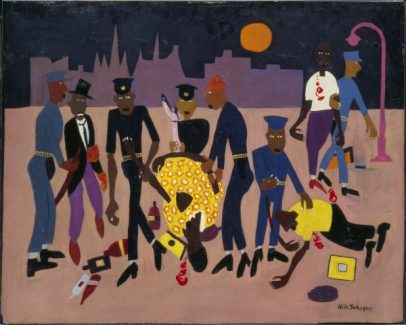

Moon over Harlem by William H.Johnson, 1943-1944 Copyright: © Washington D.C., Smithsonian American Art Museum

“The Color Line” exhibition is well worth a visit if only to see how outsiders see us. “The Color Line” comprises more than 200 objects, including paintings, photographs, films, sheet music, posters and broadsides — a plethora of printed artifacts which makes this exhibition somewhat of a teaching-centered experience. This matters because the French are taught little about the overall story of American blacks in schools (just as we are taught only glancingly about, say, the French Revolution).

“Most [French] people with education have no real idea of what racial discrimination was in America in the 20th century,” museum president Stéphane Martin said over lunch in the Quai Branly’s rooftop restaurant with its stunning view of the Eiffel Tower. “Most people believe everything stopped after the Civil War and that everything was fine. … The French were not so aware until maybe the Sixties of what was happening in the Southern states of the United States.”

The exhibition tries to put the viewer in the shoes of the oppressed, the enslaved, the victims of discrimination, but not with excessive emotional content. While there are powerful, grisly images of lynching, the art related to slavery seems more subdued. For example, there’s a pot made by David Drake, an enslaved potter, containing cotton buds; and the bucolic Robert S.

Duncanson painting “Uncle Tom and Little Eva,” from 1853, depicting a white girl’s friendship with the much older black man.

“Finding a good topic for an exhibition is not difficult; what is more difficult is to find a creative way to approach that topic,” said Martin, a former official in the culture ministry. “The curator [Daniel Soutif] is French, so he is outside the history, but loves America and had been working on jazz and American pop culture for a long time.”

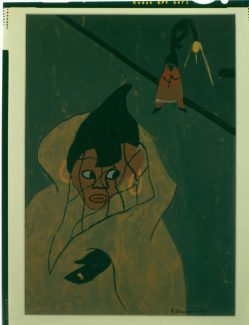

Woman in Green by Jacob Lawrence, 1937

And there is a requisite balance to be struck so as not to overpower the viewer with negative messages only. The art in “The Color Line” both shouts and whispers.

Fittingly there are copies of “The Crisis” magazine, “A Record of the Darker Races” edited by W.E.B. Du Bois. He popularized the phrase that gives the exhibit its name, writing: “The problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of color line.”

Early issues of “Crisis,” published by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, celebrate the pride and accomplishments of black leaders; the covers feature a politician, a cleric and an athlete. But in stark contrast you will see sheet music for songs like “Jimmy Crow,” (from the 1830s) and “Coon Coon Coon,” identified as “The Most Successful Song Hit of 1901,” which traffic in the worst stereotypical caricatures of the times.

Jacob Lawrence’s paintings of 1930s black life dispel the Other in their depictions of the quotidian experiences of all people: playing pool, dining at a barbeque joint, hailing an ice peddler, attending a funeral. (Closer to home, Lawrence’s magnificent “Migration Series” can be seen at the Phillips Collection through January 8, 2017.

) But in contrast, Faith Ringgold’s disturbing “The Flag is Bleeding” from 1967 shows a black man and white couple peering from behind a stars and stripes dripping blood.

There is a page from the Black Panther Party newspaper (“In Revolution one wins, or one dies,” it says) and an FBI wanted poster for 1960s radical Angela Davis. Meanwhile Rosa Parks sits placidly in her booking photo for refusing to give up her seat on a Montgomery, Ala.

, bus.

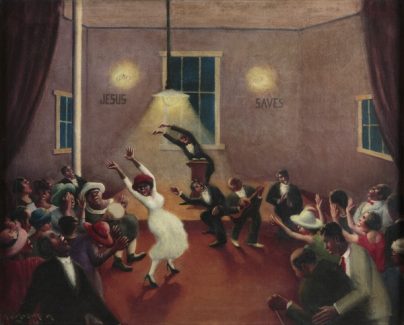

Tongues (Holy Rollers) by Archibald J. Motley Jr. 1929

The sheer quantity of materials in exhibitions such as these can be overly dense, Martin concedes, while mentioning that the curator hails from “a typical school of curators that was developed at the Pompidou Center during past 20 years.”

“Some people don’t like them because they can overwhelming,” he adds, “exhibitions which are little bit like chorus music where you can follow two different lines. In this exhibition you can follow either a purely artistic line; it can be just an African American art exhibition, which you can see in Atlanta, for example, at the High Museum. Or it can be a purely historical exhibition on history, informative.”

And provocative — for example, with its homage to the first African American world heavyweight boxing champ, Jack Johnson: “It was quite daring for the curator to address the eroticism of the black male body and the fascination in France for black boxers,” Martin says.

African American Flag by David Hammons, 1990

The Quai Branly, once described by the Los Angeles Times as “a steel-and-glass palace on the Seine River,” is a work of art in itself. It shares the tradition of creative architecture seen in Paris museums such as the Pompidou, with a design that is linked to the shadow cast by the Eiffel Tower. One wall, which faces the motorway along the Seine, features a stunning cascade of live greenery.

Anyone planning a winter trip to Paris – Christmas is a non-touristy, enchanting time to visit the City of Lights – is well advised to visit this relatively undiscovered museum and this challenging exhibition. Its overstuffed survey of the black civil rights struggle in America may be a lot to take in, but is that so bad? Stéphane Martin doesn’t think so.

“That’s was the spirit I was looking for, an exhibition that could be extremely dense.

And I guess maybe some people will be unsatisfied and feel, ‘Well, there’s so much to see that I’m not going to see everything.’” His advice: “Well, come again!

”

“The Color Line: African-American Artists and Segregation” runs through Jan. 15, 2017.