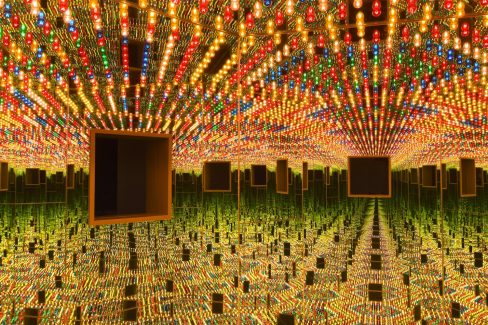

Avant- garde icon Yayoi Kusama’s “Infinity Mirrors” mesmerizes at the Hirshhorn.

Yayoi Kusama with recent works in Tokyo, 2016 PHOTO BY TOMOAKI MAKINO COURTESY OF THE ARTIST © YAYOI KUSAMA;

Yayoi Kusama’s unapologetically bold work is back in the United States after nearly two decades.The Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden will show a collection of her work through mid-May using a timed pass system to handle the crowds of eager fans hoping to set eyes on this much-anticipated installation. In addition to explosively colorful paintings and sculptures, the exhibition includes a series of mirrored rooms where Kusama’s reflected art gives the breathtaking sensation of infinity. Visitors will spend 30 to 45 ethereal seconds in each of the six life-size cubes for what curator Mika Yoshitake describes as “cosmological.” In the rooms, she says, “You really feel like you’re floating.”

Aftermath of Obliteration of Eternity, 2009 Wood, mirror, plastic, acrylic, LED, black glass, and aluminum Collection of the artist. Courtesy of Ota Fine Arts, Tokyo/Singapore; Victoria Miro, London; David Zwirner, New York. © Yayoi Kusama

Having grown up in rural Japan, Kusama seemed destined to live the traditional life her parents had envisioned, but in the late ’50s she rebelled and set out for NewYork to pursue an artistic career. It was there that her signature use of colored polka dots,“nets” and multi-reflective environments made her a pioneer on the art scene.Though critics didn’t give her work its proper due until much later, Kusama’s avant-garde style influenced Andy Warhol and other contemporary greats.

Working off the premise of controlled chaos, she creates works about “self- obliteration,” a concept which defines the trade-off between ego and equality. These dueling ideas evolved into Kusama’s famous “Obliteration Room” (on view at the Hirshhorn) – a stark, white, furnished space that visitors are invited to decorate with colored polka dot stickers.Yoshitake says the idea is to “make things unrecognizable” in order to “see things anew.”

The Obliteration Room, 2002 to present Furniture, white paint, and dot stickers Dimensions variable Collaboration between Yayoi Kusama and Queensland Art Gallery. Commissioned Queensland Art Gallery, Australia. Gift of the artist through the Queensland Art Gallery Foundation 2012. Collection: Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane, Australia Photograph: QAGOMA Photography © Yayoi Kusama

Kusama obsessively employs pattern play to physically manifest the personal demons and hallucinations she has battled from a young age. In search of structure and mental respite, she returned to Japan decades ago and voluntarily checked herself into a mental institution outside Tokyo.To this day, she spends most of her hours creating at a nearby studio in Shinjuku.

In her memoir, Kusama calls art her medicine.“I fight pain, anxiety and fear every day,” she writes,“and the only method I have found that relieves my illness is to keep creating art.” In conversations with Kusama,Yoshitake says she moves beyond the walls of her studio to speak in larger terms about love and peace, tropes repeatedly found in her work. Beyond and in spite of her mental health struggles, Kusama’s art conveys a deep optimism for the modern world.

This article appeared in the March 2017 issue of Washington Life.

Pumpkin, 2016, at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden. (Courtesy of Ota Fine Arts, Tokyo/Singapore. © Yayoi Kusama. Photo by Cathy Carver.)

Infinity Mirrored Room – Love Forever, 1966/1994, at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden Wood, mirrors, metal, and lightbulbs. (Photo by Cathy Carver)

Dots Obsession – Love Transformed Into Dots, 2007, at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden Mixed media installation. (Courtesy of Ota Fine Arts, Tokyo/Singapore; Victoria Miro, London; David Zwirner, New York., © Yayoi Kusama Photo by Cathy Carver)