From capture to conservation, “Raising America’s Zoo” tells the history of the National Zoo, beginning with its first family of gorillas.

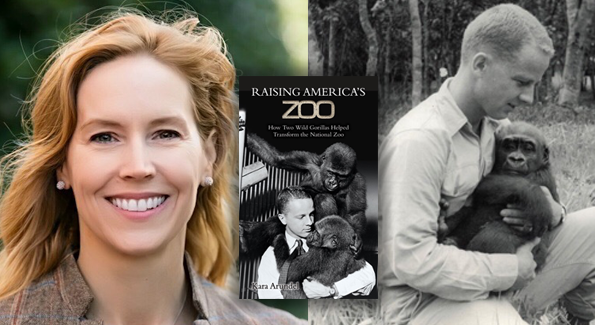

From left: Author Kara Arundel; “Raising America’s Zoo” book cover; Arthur “Nick” Arundel holding Moka, age 20 months, in the Belgian Congo in 1955.

Few people know it, but in 1955 the National Zoo was changed forever with the arrival of its first gorillas. After serving in combat in Korea for the Marine Corps, native Washingtonian and newspaperman Nick Arundel went on safari to the Belgian Congo and returned a month later carrying Moka and Nikumba in his arms. The young apes were flown from Leopoldville to New York on Sabena Airlines, where they sat on his lap and passengers took turns feeding the adorable apes from bottles.

Arundel later referred to Moka and Nikumba as his “first children” when he met his bride-to-be Peggy McElroy. After settling them in at the zoo, he would often stop by after work to play with the young apes; that is, until the day one of them shredded his dress shirt and tie with one affectionate paw swipe.

Arundel’s daughter-in-law Kara had heard bits and pieces of the story over the years, but after Nick died, she found additional details in the boxes of meticulously kept diaries, reports and letters he’d left behind. She then spent five years researching at the Smithsonian Archives while interviewing zoo staffers to get a full history of the transformation of the National Zoo from “a menagerie type park to an internationally respected center focused on conservation of both captive and wild species,” as her book describes it.

“Raising America’s Zoo” (Mascot Books) is Kara Arundel’s first book and, as with most first endeavors, proved more challenging than anticipated. While “there are probably 30 panda books,” she is certain this is the first to focus on the gorillas.

“It’s an under-told story and a great local story, because I write about the role that the city and the federal government had in supporting the zoo,” she says.

Her personal connection to Nick Arundel makes the book more captivating than a typical history, as stories of his colorful youth and philanthropic endeavors are intermixed with statistics and factual insights on the zoo’s evolution from its founding in 1889 to the present day. Her father-in-law helped establish Friends of the National Zoo (FONZ) in 1958, a nonprofit organization that helps to save species and raise funds for the zoo, which doesn’t charge admission fees.

The book doesn’t gloss over the barbaric methods once taken to obtain wild animals.

Whether the attainment of the zoo’s first family of gorillas was the result of a bloody safari or a generous gift from an international government is a question that remains unanswered.

“I almost quit writing because I didn’t definitely have that story,” the author admits, “but then [I realized] … it is really a parallel story of Nick and the zoo, moving away from the time when animals were captured through very violent methods and brought back.”

Now, she says, zoos are working together to focus on conservation. They’re very organized in how they manage and breed species like gorillas.

Nick, she says, was one of the staunchest advocates for change. He was close to the gorillas until they died and when he passed away peacefully at home in 2011, a photograph of himself proudly holding Moka and Nikumba hung outside his bedroom.

Arundel hopes readers will go away with a newfound appreciation for the National Zoo, thanks to the perseverance of its dogged employees to create an atmosphere more humane for animals.

This story ran in the October 2017 issue of Washington Life.