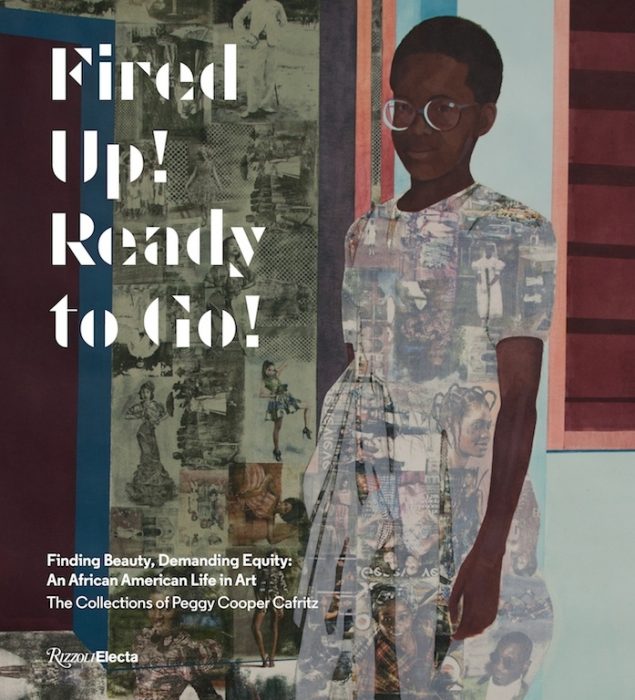

“Fired Up! Ready to Go!” features the collection of the late patron of the arts Peggy Cooper Cafritz.

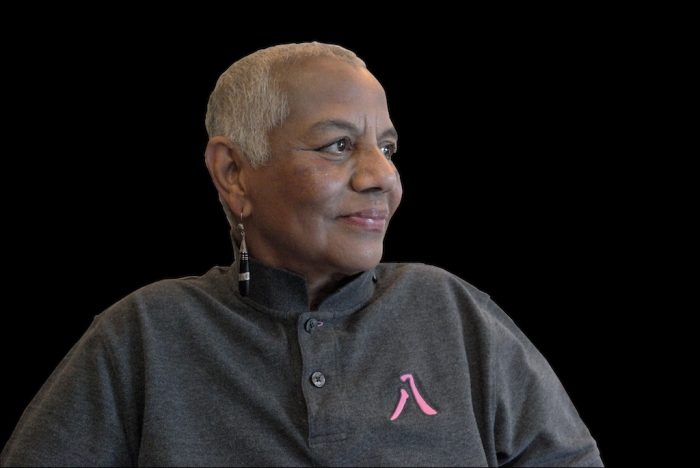

Peggy Cooper Cafritz (Photo Courtesy Marqueo)

“The absence of equity diminishes beauty,” Peggy Cooper Cafritz wrote in the introductory essay to “Fired Up! Ready to Go!” (Rizzoli). Before her death at age 70 in February of this year, one of Washington’s most generous philanthropists, activists and arts patrons published the book highlighting her collections. Cooper Cafritz, who was born in Alabama and lived through segregation, devoted her life to championing artists of African descent. Her massive trove of paintings, sculptures and other works was one of the largest of its kind until, in 2009, more than 300 pieces were lost in a fire that destroyed her Northwest home.

It was the largest residential fire in D.C. history.

But if Cooper Cafritz was discouraged, she didn’t let it show.

She quickly rebuilt the collection, gathering works from such artists as Jacob Lawrence, Kara Walker, Kerry James Marshall, Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, Carrie Mae Weems, Nick Cave and Kehinde Wiley, who recently painted Barack Obama’s official portrait.

She gravitated “toward art that is difficult and poses critical questions,” artist Jack Shainman explains. Themes such as slavery and police brutality are present in the striking pieces that lined her walls.

Cooper Cafritz collected, in part, “as a political act of solidarity — a necessary step toward a more permanent space for artists of color on museum walls,” contributor Kerry James Marshall observed.

She embraced conceptual art at a time when many were not so bold.

Kara Walker’s “A Warm Summer Evening in 1863” (2008)

“Fired Up! Ready to Go!” includes glossy photos of her artworks both before and after the fire (200 images in total) alongside essays by Cooper Cafritz, artists who were close to her, curatorial analyses and an in-depth interview with Studio Museum director Thelma Golden.

Golden was struck by Cooper Cafritz’s eye for art, once expressing as much to her: “Many collectors collect from their eye, some collect from their heart, some collect from their intellect. You have always collected with all three.”

“I always say it’s gut, eye, mind and heart,” Cooper Cafritz responded.

The “heart” portion is key; it’s the collector’s kindness and generosity that so many remember.

Cooper Cafritz would frequently attend shows to seek out underrepresented artists with promise whose careers she could bolster.

Many speak of her as a mentor who offered guidance as well as financial backing.

“Peggy was not the first to collect my work; however, she more than anyone else has helped me to cultivate the confidence and fearlessness required to establish my career,” artist Simone Leigh wrote in the book. This was no surprise to those who knew her best for founding the Duke Ellington School of the Arts in 1974, a renowned District high school that has produced such talents as Dave Chappelle and has a majority African American student body.

Alexandre Arrechea’s “Havana” (2016)

Her legacy, Cooper Cafritz said, is her children, grandchildren and the students of Duke Ellington, who are closer to seeing equity in art:

“I thought it was so important for us to see ourselves in the context of beauty, and things that would make us question. I always knew that— that I would surround them with beauty and our history from the very beginning.”

This story first appeared in the April 2018 issue of Washington Life.