Anand Giridharadas’ “Winners Take All” investigates the global elite trying to change the world, while keeping themselves rich.

It’s no secret that the United States is plagued by extreme wealth inequality. Ten years after the financial crisis, the only people who have recovered are the top one percent, while 99 percent of Americans are 30 percent poorer than they were in 2007. The average pre-tax income of the top tenth has doubled since 1980 while the earnings of the bottom half of Americans has remained virtually the same. Some readers will be in that top ten percent and are aware of such statistics. They are also likely to be philanthropic and may be speaking up for social causes. But are those at the top willing to disrupt the status quo to make the world a more equitable place?

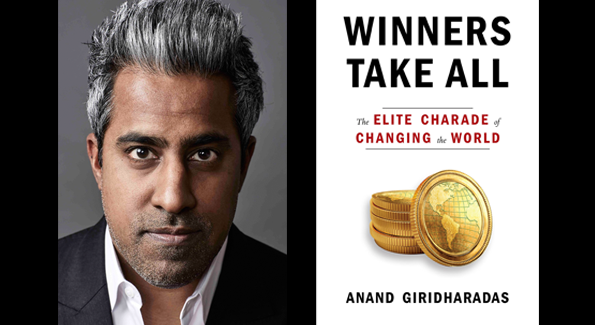

Or are the wealthy just making things worse to make themselves feel—or look—better? Journalist Anand Giridharadas asks these questions in his new book “Winners Take All: The Elite Charade of Changing the World,” which goes inside the world of the “billionaire saviors,” from tech-world thought leader conferences to black-tie fundraisers and the halls of Georgetown University, where elite students are recruited by finance companies selling a message of altruism. I spoke to the author and MSNBC political analyst to discuss.

YOU SAY THE BOOK IS THE INTERSECTION OF AN OBSERVATION OF SOCIETY AND A PERSONAL EXPERIENCE. WHAT WAS THE OBSERVATION?

I was a foreign correspondent for the New York Times in 2009 and moved back to New York in 2009. We were very much in the depths of the economic crisis but also in the depths of a longer generation-long crisis that had made the American Dream feel so elusive to so many people. It was very clear that something fundamental in this country had been lost: people’s sense of being able to make a better life for themselves. And at the same time, we live in this age of heroic generosity, all these people giving money away and all these young people wanting to change the world and everybody gravitating to buying a tote bag or TOMS shoes that make a difference. I couldn’t square those things in my mind—how is it that we live in this age where everybody seems worried about making a difference and yet it’s the most unequal time in 100 years, the angriest time in a long time? All the economic data suggests it’s basically impossible for many people to actually work hard, play by the rules and get ahead. I became interested in the way in which generosity might not just be a drop in the bucket against that injustice but would actually be part of how we uphold an unjust social order.

AND THE PERSONAL EXPERIENCE THAT LED TO THE BOOK WAS AN ASPEN INSTITUTE GLOBAL LEADERS FELLOWSHIP IN 2011. WHY WAS THAT EXPERIENCE A CATALYST?

I jokingly call it a benevolent secret society. These fellowships have become very common, and this one was about grooming young business leaders to be change agents. I was not a business leader, but in every class of 20 or so people they throw in a couple who are not—for spice and entertainment. As I got into that world and went to the Aspen Ideas Festival and saw it was sponsored by Pepsi and Monsanto in the Koch brothers seminar building discussing how to make the world a better place, it seemed like something more complicated was going on when the rich and powerful get together to make a difference. I got curious about what really happens when rich people don’t just try to make a difference but almost take over the work of social change. The Aspen Institute asked me to give a speech and I gave a surprise one critiquing many of us in the room, myself included, who come to these places and talk about making a difference but in many ways are part of keeping things fundamentally the same.

HOW DID YOU APPROACH TURNING THAT CONTROVERSIAL SPEECH INTO A BOOK OVER THREE YEARS?

The speech was an argument and, for the kind of books I do, an argument should be a very small component of it.

People have their own ideas. They don’t need to be lectured by other people’s ideas. I don’t think that moves the needle on what people think. What I’ve found is there’s no substitute for reporting, for getting into rooms that other people can’t because you have that access, and actually bothering to figure out what other people think. I had to take the argument of that speech and go back to the beginning, not to start with the answers but to start with the questions. How do you square Mark Zuckerburg talking about giving all his fortune away, building community, empowering people, with the fact that it’s the most predatory monopoly on earth? How do you square all of the paraphernalia of elite kindness with the reality of elite predation? Those questions began my inquiry but I decided to answer them not by sitting in a room and thinking but by spending time with people in these worlds. There’s an old tendency when people write about inequality to write about the poor. We think those stories are more exotic, but it occurred to me—why do we write about inequality from the vantage point of the people merely living in it instead of the people who architected it? Let’s hear from the people who built the system. In writing about the poor it almost makes it seem like they made this but they didn’t. They were the least responsible for creating the world they live in, so I thought it would be a quietly radical act to write about how rich people think about the world they built. I thought, enough poverty porn, let’s do some philanthrocapitalist porn.

WHAT DID YOU FIND OUT ABOUT HOW THE ELITE (THE “WINNERS?”) VIEW THE WORLD?

Most of the people I write about are hyper aware of being in an age of inequality, and almost all of them want to respond to this. They give back at historic levels, run programs, volunteer, and you could make a strong case that they do more than most previous elites in history, but what is also true about them is that they tend to give and help in ways that absolutely protect themselves. They give self-preservationally.

They give in ways that protect their opportunity to keep taking.

SHARE SOME EXAMPLES OF ELITE SELF-PRESERVATIONAL GIVING?

They give to charter schools but they don’t support a movement to fight for equal public schools for all. Why is it that Chevy Chase has public schools funded at like $20-$30,000 a year per student and how much are the schools in Southeast funded at? Generally rich people will support a charter school and get on the board and help some kids go to college but they will not fight for the thing that would equalize it for everybody.

Why? Because at the end of the day they don’t want to see Chevy Chase public schools brought down to the level of the average. That’s painful, that would require sacrifice, that’s not a win-win. Also, the issue of empowering women. We know from about 15 countries in the world that do this better than us, it’s not that complicated what actually empowers women: things like maternity leave and certain healthcare policies, but those things would be … expensive or require sacrifice by winners for the common good. There’s a light facsimile of change that is free or cheap and the winners gravitate to those as a way, consciously or unconsciously, of staving off the more expensive kind of change.

YOU’VE SAID THAT ALL OF THIS WAS ONE OF THE FACTORS THAT LED TO THE ELECTION OF TRUMP.

A lot of rich people on the right and left who try to change the world and make a difference through their giving enabled him in two ways. They promoted fake change over the last several years at a time when we needed real change, needed to figure out what to do with all the people displaced by trade and automation and the communities where mobility had ground to a halt. We needed to figure out education. Climate change is an education problem. All these issues are linked. In this period of declining mobility and the American Dream falling out of people’s reach, rich people generally responded by richsplaining to them that all was well, that you were wrong about your own reality, things were getting better and you just had to sit down and shut up and lean in. Selling fake change when real change is necessary just widens the gap, just makes the problems bigger and deeper and makes them fester, and I think it’s hard to understand the rise of Trump without understanding all those problems that were festering for 20-30 years instead of being addressed.

HOW DID TRUMP APPEAL TO HIS VOTERS?

Trump basically embodies this notion that he can fight for the forgotten man and woman of this country but he can also enrich himself from his hotels and golf courses and there’s no tension. His enrichment and the enrichment of the forgotten are the same. That win-win is at the heart of this book and he didn’t start that idea…Trump rode the coattails of a lot of billionaire saviors who were pushing this phony change for a long time.

THIS MAGAZINE IS READ BY THE WASHINGTON ELITE. IS THERE ANYTHING YOU WANT TO SAY TO THEM DIRECTLY?

One thing to think about is that I think seven out of the 10 richest counties in America encircle Washington.

That’s a very, very bad indicator. The city designed to create real change is not supposed to be a place where cash is the prize. The seat of democracy has basically been captured by people who have figured out how to make money by being approximate to the system…The purpose of the city is to represent the rest of the country, and it clearly is failing to do that in a way that is so spectacular that a nincompoop demagogue is now in charge of the most powerful country in the history of the world.

WHAT SHOULD THESE WEALTHY WASHINGTONIANS BE ASKING THEMSELVES?

Washington is as good a laboratory as any city in America for the ways in which we talk about change as elites, but cling to our much better schools in Alexandria and Chevy Chase while solving problems for ourselves and not for everybody at the root and make requisite noises about liberty and justice for all while in fact working as lobbyists or in various other capacities to continue the great rigging of America. One question that I would ask anyone reading this interview to consider is your regular life, not your side job, not your moonlight charity project, not what you donate to St. Jude’s, is your regular life right now on the side of making America more equitable. Are you working for the rigging or the de-rigging? It’s that simple. If a lot of your readers ask themselves that, they may not be happy with their answers. I wrote this book to not attack people but to actually allow them to hold up a mirror because the way we have always made change in America is a combination of movements from below demanding rights, demanding justice, demanding change, but also a certain number of people within the power structure being honest enough and brave enough to look at themselves and say I’m not living the values that I believe in and I want to do better.

This interview has been edited and condensed. It appears in the October 2018 issue of Washington Life Magazine.