The Little and Big Indignities of Being a Black Man in America.

By Jeffrey James Madison

George Floyd’s death has had a weird effect on my white friends. They’re all walking on eggshells, as if asking how it affected me might violate some unspoken right to personal anguish. Honestly, it’s maddening. Finally, two weeks after the murder sparked mass outrage, a lifelong white friend admitted he “was scared to ask,” so he didn’t.

On my probing, he explained that he didn’t want to make me relive something traumatic. “Perhaps,” he said on second thought,”I tell myself that so I can avoid the subject.”

My sense is that this friend is afraid to find out that somebody close to him has also been victimized by the police. Learning that truth might pop the bubble protecting his perception of our shared reality.

Friends and colleagues might describe me as affable, intelligent, even generous — the same adjectives used to sum up George Floyd by those who knew him best. People want to believe that individuals with such qualities enjoy pleasant, police-encounter-free lives.

I told said friend it was okay to ask how I was feeling and furthermore, about the indignities I’d experienced as a Black American man. So he did.

There’s an old Swahili saying, “haba na haba, hujaza kibaba,” which literals translates to “little by little, the container gets filled.” It could mean water in a jug or it could refer to little indignities that gradually fill up a soul.

There’s an old Swahili saying, “haba na haba, hujaza kibaba,” which literals translates to “little by little, the container gets filled.” It could mean water in a jug or it could refer to little indignities that gradually fill up a soul.

Little indignities like when my parents moved our family into an all-white, upper middle class, Northwest Washington D.C. neighborhood after my sixth birthday and five little white boys greeted me, my twin brother and eight-year-old sister by calling us the N-word.

Or little indignities like the time a few years later at a North Carolina hotel swimming pool when I eased into the water–and all the white adults scrambled out, pulling their children along with them.

Or in 1981, when I presented cash to a bank teller asking her to issue me a cashier’s check made out to Harvard University, and she returned it made out to historically Black Howard University, twice.

Or later that same year, while crossing the street near my Harvard dorm, when a white woman in her car locked her doors as I walked past.

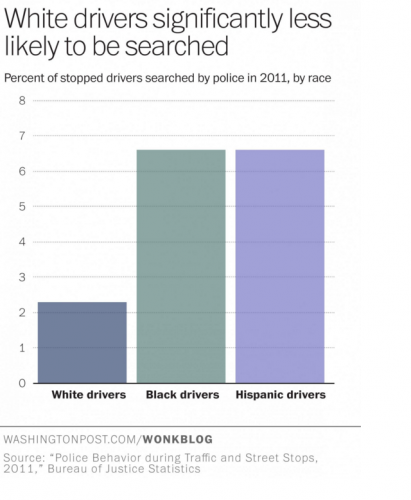

Within a year of moving to Los Angeles after college, I’d been pulled over twice for speeding. And by “speeding,” I mean barely keeping up with traffic in my 1981 Mazda station wagon hoopty. Unlike white drivers I’d witnessed receiving citations from the comfort of their cars, I was ordered out of my vehicle and forced to stand against the freeway’s concrete barrier, arms out, palms up while my car was searched.

In 1992, the police pulled me over for “failure to yield on a left turn.” Again, I was ordered out of my car and threatened with handcuffs.

I talked my way out of that, but not before having my plates run, my car searched and my humiliation publicized.

By February 1993, I’d traded the Mazda for a brick-red, 1955 Chevy Bel Air, a massive car that resembled a New York City Checker cab. I was driving solo, dressed in a suit, headed form work to my engagement party. I turned left–on a green arrow–when suddenly a cop car lit me up with lights and sirens

I pulled over, slid my driver’s license and registration onto the dashboard and raised my hands palming the car’s ceiling, as I’d done in previous situations. A second place car arrived and aimed its spotlight on my rear-view mirror. The other spotlight was aimed at my side, blinding me completely.

Even as my arms, shoulders and back ached from keeping my hands raised for 20 minutes, I didn’t dare move. Finally, the spotlights turned off and I saw an officer standing at my driver’s side window alongside six patrol cars and a SWAT team.

I was instructed to exit the vehicle and step to the curb. When one cop reached for his handcuffs I told him that I would keep my hands where he could see them sans cuffs and I demanded to know why I’d been stopped.

He holstered his cuffs and bit his tongue. As ten more silent minutes passed, I counted 13 officers and six SWAT members on the blocked off street. A sergeant approached and I repeated my question. A red sports car with two Black men inside was seen fleeing the scene of an attempted carjacking of a white man in a Porsche, he said. While pointing to my large four-door sedan, I noted that I was the only person in my opposite-of-a-sports-car vehicle. His response? “Somebody might be hiding in your trunk.” Incredulous, I reached for my car keys at which point every single cop drew and pointed their guns at me. “Freeze!” they yelled.

But they didn’t have to. There’s a distinctive sound made when that many hands slap holster leather and SWAT members yank their long guns level. It stopped me cold. I shot my hands skyward.

“There’s nobody in my trunk,” I said. It sounded more like a plea than a statement. As the sergeant grabbed my keys and approached the trunk, all weapon barrels moved off me and trained on it. Unlock. Open. Empty.

Moments later, SWAT, police and bystanders who’d gathered around the scene all quietly receded into the dusk.

The sergeant handed me back my keys, ducked into his squad car and drove away without a word. No apology. Nothing. I was left alone to gather myself together enough to drive to my fiancée’s house and explain why I had just missed our engagement party.

I cannot recall anything from the rest of that night nor the next few days. I shared this encounter for the first time recently with my twin, who has had his own police confrontations. He thinks I may have post-traumatic stress disorder.

Courtesy of the Washington Post

Whether I do or don’t, I cannot say. What I can say is that my stories are but a handful of the countless indignities that I have experienced as a Black man in America. I promise you they are not unique to me. Affable, intelligent, maybe even generous — many of the Black men you know likely have similar tales. Ask them. They might share it. It helps relieve the emotional pressure from those indignities that “haba na haba, hujaza kibaba” of our souls.

My white friend expressed outrage, disgust and despair over my stories. I knew those feelings. We know them as living while Black.

I let hims keep in his emotions for several quiet minutes. Then I admitted that despite all the Black lives that have been taken by police, culminating with the inconceivable on-camera killing of George Floyd, this time I felt cautiously optimistic about true change occurring in this country.

“Why now?” he asked.

May 1963 shocked the collective conscience of the nation. The momentum of the civil rights movement accelerated quickly once the nightly news aired images from Birmingham, Alabama showing the unbridled brutality of water from firehoses slamming people into walls and German shepherds attacking innocent bystanders. No longer could white people wonder if the stories were true, no longer could they think maybe “those Negroes might have been exaggerating just a bit.”Yes, the stories were true. No, Black folk weren’t embellishing.

In May 2020, it happened again. The unrelenting way that Derek Chauvin stared into the unwavering lens of the camera phone as it recorded him killing George Floyd for the whole world to witness catapulted us into a new, permanent era of police reform the same way. That grainy footage from 57 years ago pushed civil rights to the forefront of the American psyche. No longer need the world wonder if these stories of police brutality are really true, or wonder if Black folk might have been exaggerating just a bit.

No longer can respectable white people sit idly and live with the indelible image of police brutality and not feel compelled to act.

Despite the horrific scene from that Minneapolis street corner, I find strength in the peaceful protests that rose up in its wake because it’s no longer use us Black folk on the front lines. I see good white Americans awakening and coming to the aid of their fellow countrymen.

I pray they are all awake enough to avoid the temptation of hitting the snooze button like they did after Garner and Martin and Bland and Brooks and …