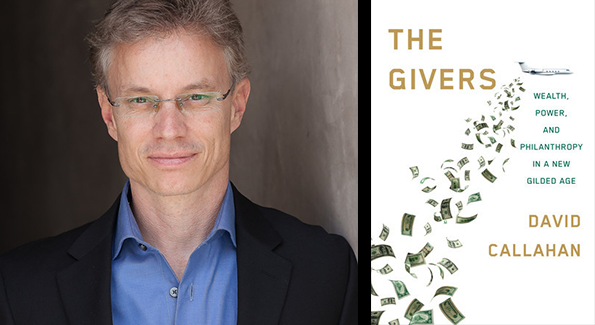

David Callahan explores the influence of elite philanthropy on American life in ‘The Givers.’

David Callahan author photo by Sylvia Spross

“With great wealth comes great responsibility,” Bill Gates once said. It’s a sentiment that American philanthropists are embracing more and more – while they are still living.

Activist donors on both sides of the political aisle are taking over where government is lacking, tackling the big issues of the day (climate change, school reform, cancer research, etc.

) with their charitable dollars. Inside Philanthropy founder David Callahan introduces us to this new class of donors in “The Givers: Wealth, Power and Philanthropy in a New Gilded Age” (Alfred A. Knopf) and investigates what this power shift means for ordinary citizens.

What inspired you to write this book?

I’ve long been interested in the influence of philanthropy, going back to the 1990s when I began working in the think tank world and saw how effective these donor-supported institutions could be in swaying public policy. In 2014, I started Inside Philanthropy and began looking at the rise of new givers with big ambitions to shift the direction of society. This book grew out of that reporting.

Mark Zuckerberg and Priscilla Chan got a lot of backlash for establishing an LLC for their giving rather than a foundation. Why is that? Should we be skeptical of philanthropists who give that way?

LLCs make people nervous because they are less transparent, so it’s hard to see what donors are doing. But philanthropists have some good reasons for using LLCs because they can use their money more flexibly – such as investing in for-profit social enterprises alongside traditional grantmaking. You can also make political gifts through LLCs, which you can’t do with foundations.

More philanthropists are embracing “giving while living” as you put it, rather than leaving money to their kids or putting it into foundations that go on long after they die. What does this change mean for the country?

This shift reflects a rising desire among donors to solve big problems or make “systemic change” in society – hopefully sooner rather than later. That’s a different goal than stewarding existing institutions or supporting particular cities or regions, and it leads donors to give more aggressively while they’re still living.

Philanthropists like the Koch brothers are more interested in shaping public policy than ever before. How significant is this influence on our politics, and is it growing?

Often charitable gifts to think tanks, advocacy organizations and legal groups are more effective in bringing about change than political donations.

Charles Koch said this himself. There are lots of examples of philanthropy-backed nonprofits playing a big role in policy changes, such as when legal groups challenged the Affordable Care Act and got a key piece of that law, mandating expansion of Medicaid, struck down by the Supreme Court.

Name a single philanthropist who’s been most effective with his or her giving.

Michael Bloomberg is an especially effective philanthropist. He’s focused a lot of resources on solvable problems like reducing tobacco-related deaths in poorer countries and stuck with this work over a long period. He’s also made big bets, such as backing the Sierra Club’s effort to shut down coal-fired power plants on a large scale.

What is the biggest mistake philanthropists make starting out?

Many spread their gifts too widely and without a real strategy, as opposed to focusing more narrowly and being strategic. One problem is that newer donors may engage in too much “relationship giving” – backing an array of organizations that are recommended by friends as opposed to a select handful that are the most effective.

You outline areas of reform for a more transparent, accountable and “less aggressively political” philanthropic sector. Will you briefly describe these?

Too much money is flowing in opaque ways through donor-advised funds that aren’t governed by the same strong disclosure rules as private foundations. All institutions that make grants should be fully transparent. We also should seek to limit the rising flood of giving aimed at influencing public policy by tightening the criteria for what organizations can receive tax-deductible gifts. Many 501(c)3 policy groups should probably be reclassified as 501(c)4s, which are not eligible to receive tax-deductible gifts.

This interview appears in the June 2017 issue of Washington Life.