To give away money is an easy matter and in any man’s power. But to decide to whom to give it and how large and when and for what purpose and how, is neither in every man’s power nor an easy matter.

” So wrote Aristotle some time around 350 B.C. In

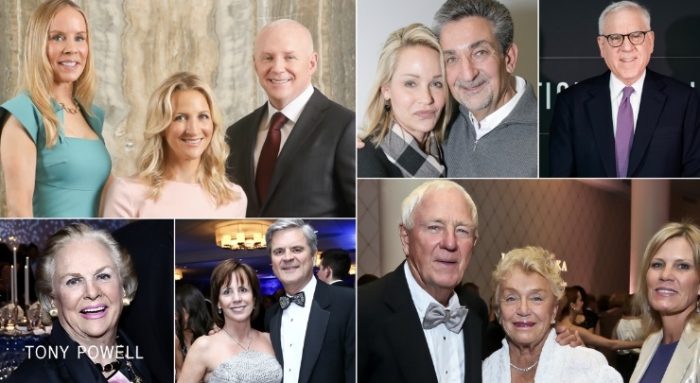

2018, philanthropists face the same challenge. If the fundamental decision confronting givers is rooted in ancient history, much else has changed, and continues to change, in what is being called the “Golden Age of Philanthropy.” The 50 leading philanthropists from the greater Washington area listed below reflect some of those changes, representing – for example – both so-called “old time charity” as opposed to more hands- on involvement with the recipient to ensure the proper use of donations and to keep close track of their impact.

In the United States in the past couple of years, giving has reached unprecedented levels, marginally less in 2017 than in the previous year, but still well above levels when philanthropy was hit by the global crisis of 2008-2009.

On average, greater Washington, D.C. area residents gave 3.5 percent of their income to charity and favorite causes, and, lacking the enormous wealth of New York City or Los Angeles, the area still ranked fourth in philanthropic funding nationwide. Foundations, many of them established by area families, total close to 2,000. Twenty years ago, they were in the middle hundreds.

Such generous donors set an example for us all, and are listed here. Education has long been, and remains, the most popular philanthropic cause for ultra-high-net-worth Washingtonians.

With college tuition fees going through the roof, and government involvement dwindling, philanthropic support for higher education, especially for lower income students, is increasingly in demand. But nation-wide, according to Giving USA 2017, the three main sectors that received philanthropic donations were: religion (32 percent), education (15 percent) and human services (12 percent).

What would industrialist Andrew Carnegie, patron saint of American philanthropy, make of new philanthropic vehicles, including online platforms, donor-advised funds, LLCs and crowd-funding, driven largely by technological change? Carnegie was 65 when he turned his attention to philanthropy, and retirement age used to be the time to take up charitable giving in earnest. But as high tech pioneers have gotten rich quicker, the ultra-wealthy have started to give at younger ages.

According to financial wealth experts, many new generation philanthropists don’t just give money, they seek more involvement in the decision making process with regard to how their dollars are spent.

In so doing they often bypass the usual channels to their targeted causes, the foundations and funding networks, and donate directly to the cause itself. Their models for so-called “involvement philanthropy” are Bill Gates, Mark Zuckerberg and others who “focus on personal direction with little significant community input and accountability,” says wealth consultant and philanthropy expert Martin Levine.

The other game changer in philanthropy has been the growing number of super-rich women involved with charitable ventures of every kind, but in particular those addressing issues facing women and girls.

Recent research shows that at every income level women donate almost twice as much to charity as do men. “Women have resources to pay for change, to direct their own movies, to do their own research, to tell their own stories, and they are doing it in droves,” Cynthia Nimmo, president and CEO of the Women’s Funding Network told Forbes magazine.

Culture is another focus area for Washington philanthropists. Every major city in Germany has its own opera house, funded by the government. But the Washington National Opera depends for its survival on the generosity of a handful of rich patrons. The U.S. government has never seen it as its role to support culture in any significant way – less so under the Trump administration, which threatens to cut off money for cultural institutions altogether.

But the vision of billions of private dollars pouring into philanthropic causes also has its skeptics – not to say critics, especially when such advocacy is seeking radical change in social areas where government is also involved. Some big philanthropic campaigns question whether money is more powerful than the vote. That is why, in the early American republic, some leaders sought to outlaw philanthropy. They believed that private money with public goals would corrupt democracy.

That is also why a hundred years ago, John D. Rockefeller had a hard time getting the Rockefeller Foundation’s charter approved by a wary Congress. A recent Schwab survey found that despite 60 percent of respondents saying the Washington metropolitan area is one of the most expensive in the country when it comes to cost of living, a majority of residents still view charitable giving as an essential part of their lives.

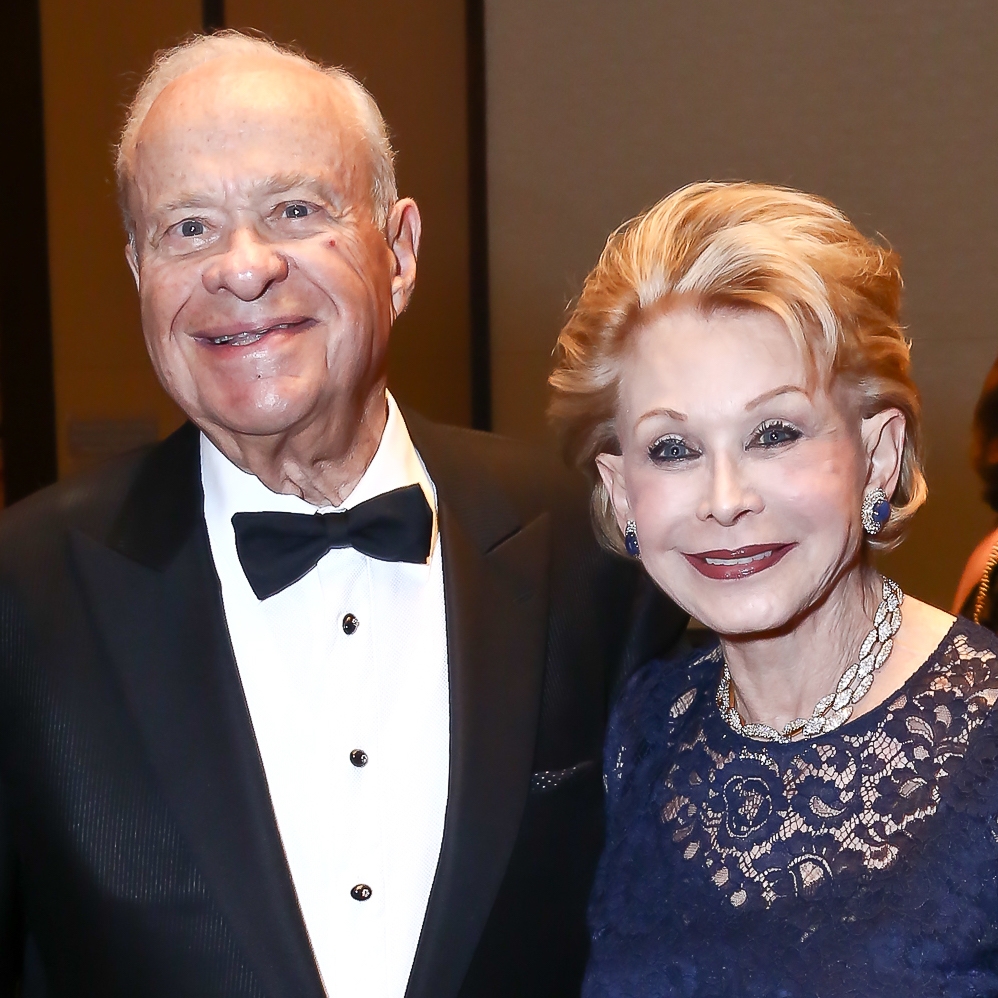

There is probably no better anecdote of the immense giving profile of Washingtonians than the $26 million raised in one night last month for the Inova Schar Cancer Center. NVR President Paul Saville and his wife Linda and their 225 guests set a record in the Washington area for a single-event non-profit fundraiser.

Guests at the closed-press event pitched in $25,000 per couple to hear a discussion on politics and the future of genomics in medical research and application, led by President George W. Bush and former White House advisor Karl Rove. The record haul helped support the opening of a new highly personalized cancer research and treatment center on Inova’s new 117-acre campus.

Now that, dear reader, is the definition of philanthropy.