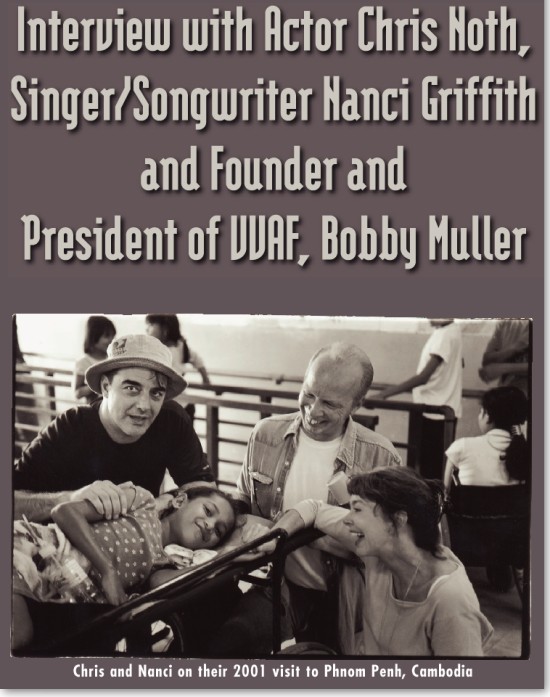

The U.S. Department of State estimates that 60-75 million landmines remainlittered over half the world’s countries. A landmine can last up to a centuryin the ground, unless it is removed or more commonly, detonated by an innocent childplaying in a field or a poor farmer working the land. Some landmines cost only$3 to produce but as much as a $1000 to remove, and for every 5,000 mines cleared,one de-miner is killed and two are injured. Officials at the Pentagon claim landminesare needed to protect U.S. troops and therefore resist banning landmines, but studiescommissioned by the Pentagon show otherwise. Landmines caused 30 percentof the casualties in the Persian Gulf War, one-third of the U.S. deaths and injuries inVietnam (64,000), and since military operations began in Afghanistan, landmines havekilled 15 U.S. soldiers. Vietnam Veterans of America Foundation (VVAF) is a non-profit, non-governmental organization,founded in 1980 by Bobby Muller and John Terzano, both veterans. It is dedicated to achievingglobal security through programs that promote justice and freedom, and reduce the worldwide threatposed by war. VVAF’s programs assist innocent civilian victims in 14 war-torncountries by providing physical and social rehabilitation services as well as identifyinglandmine clearance priorities. In 1991, VVAF co-founded the International Global Campaign to Ban Land Mines, whichwas awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1997. To capitalize on the award and to furtherraise public awareness, VVAF established Campaign for a Landmine Free World. TheCampaign raises money for its programs and increases awareness through concerttours. Some of the artists and celebrities have included Nanci Griffith, Chris Noth,Mary Chapin Carpenter, David Burn, Elvis Costello, and Emmylou Harris, to name afew. VVAF’s Sports for Life and Campaign for a Landmine Free World is the benefitingcharity for this year’s Saks Fifth Avenue and Washington Life magazine “Men ofSubstance and Style Awards.” Washington Life’s editor, Nancy Bagley, recently spoketo Bobby Muller, Nanci Griffith and Chris Noth about this international humanitarianorganization and some of its programs. Nancy Bagley:Some people might misperceive VVAF as a Veterans organization that helps veterans because of itsname. However, in reality it was started by you, Bobby and John Terzano, bothveterans, to help the very people that you were fighting against. What prompted you to do this? Bobby Muller:We started as Vietnam Veterans of America trying to address theneeds and concerns of the Vietnam veterans. We led the first group of Americanveterans back to Vietnam 22 years ago. We were going back to find out what the consequenceswere of the usage of oxi-herbicides, commonly known as Agent Orange. Becausewe couldn’t get answers from our government regarding our own population, wesaid, “Let’s go to Vietnam where the stuff was used.” We also had concerns with thevery public issue of accounting for the missing. And we had a third agenda, the ideathat we could begin the process of reconciliation. On that first visit, we were struck bythe horrific situation in Vietnam. The war in many ways had not ended for Vietnam.The economic embargo and the political isolation that resulted were devastating. And onan absolutely human basis, we felt a strong need to address what was clearly a legacy ofour war, and help the other victims of war recover in their own lives and as a country.It was as simple as that. NB:So then how did VVAF become the organization that it is today? BM:We realized that we had to get beyond our own needs and address the other victimsof war. To do that, we needed to separate the role of the membership organization thatwas there to address the immediate needs of the Vietnam vets, and the Foundation thatwould address the broader aspects of war, including humanitarian assistance and reconciliation.Our work with Vietnam brought us into neighboring Cambodia which led usto understand the story of Cambodia better, and we recognized it was truly the greatertragedy of our war in Indochina overall. NB:Nanci, how did you first become involved with VVAF? Nanci Griffith:I got interested in landmine issues because of Princess Diana andthen Emmylou Harris connected me to Bobby and all the folks at VVAF. My firsttrip to Cambodia and Vietnam was with Sheryl Crow. My ex-husband was one of myreasons for wanting to go. He’s a Vietnam veteran. NB:And what about you, Chris? How did you get involved with VVAF? Chris Noth:Through my relationship with Nanci Griffith. NB:So do you do anything Nanci asks you to do? CN:Well, we are mutual fans. She’s a fan of my work in Law and Order and Sex inthe City and I’m a fan of her music, and we’ve had a friendship for years. She askedif I wanted to go to Vietnam and Cambodia and see what VVAF was doing. NB:Bobby, we are about to enter into a war in another faraway land, andAmerica has recently seen firsthand in Afghanistan the necessity of what we call“nation building.” However, don’t landmines make the job of postwar recoveryand development more difficult? BM:One of the reasons we began the campaign to get rid of landmines was becauseof the recognition of how widespread and how profoundly affecting the existence oflandmines are to a country. Everybody from the international relief and developmentcommunity to the World Bank cites landmines as a factor in their program effortsto improve the situation in these countries post-conflict. Landmines go way beyondthe individual victims, in terms of being a devastating weapon. It is a weapon that haseconomic consequences. Landmines deny principal assets for developing countries:productivity of their land, and the ability for people in commerce to move around thecountry.Its overall consequences are economically and socially devastating. NB:Then why won’t the U.S. sign the international landmine treaty that somany other countries have signed? BM:The United States does not really, today in particular, want to be constrainedby international agreements, international law, international mechanisms, or institutions,and it is therefore pretty much guaranteed that this Administration will neversign the international agreement regarding landmines. NB:Okay, then why didn’t past Administrations sign it? BM:Their concern was not this Administration’s concern with internationallaw and agreements, but more the second driving political argument, which is thatthe military simply does not want to establish the precedent of society getting intothe business of deciding which weapons are appropriate for the military to use. We havehad many, very honest, closed-door discussions with the military, and they have saidquite frankly, it has nothing to do with landmines. It has everything to do with avoidingthe establishment of a precedence. So, when you have the nation’s leading retired militaryfigures, like the hero of the first Gulf War, Norman Schwarzkopf saying that weshould get rid of landmines for the protection of our own forces, and they still don’tdo it, you have to look at the fact that there is another consideration beyond the obviousinadequate military benefit of using landmines. NB:I understand that you both [Chris and Nanci] had a great experience at theJuly 2001 Rockin’ Along the Mekong concert in Cambodia. NG:That was fantastic. It was really wonderful to play and actually do a concertin Pnomh Penh with Dave Alvin, and I also enjoyed playing in Hanoi with theVietnamese National Chamber Orchestra. I would say that was one of the definingmoments of my career. NB:Oh really. Why? NG:I sang a song I wrote on my first trip to Vietnam with Sheryl Crow called “TravelingThrough This Part of You.” CN:The concert was fun, but it was the other things that I was shown along the waythat were a little more interesting for me. NB:Like what? CN:Well, like going to the VVAF school, and silk farm, and the clinics in KienKhleang and Prey Veng and Preah Vihear. NB:What’s special about them? CN:Seeing people initially come out of the hills and jungles without limbs to betreated, and then learning how to treat other people. NB:What do you mean,“learning how to treat other people”? CN:I mean VVAF teaches victims to make prosthetic devices and wheelchairs for otherlandmine victims. It’s completely, for lack of a better word, recyclable. NB:VVAF provides a lot of the survey data to organizations that actually do thedangerous job of de-mining fields and farmland in landmine-infested countries.Is that correct,Bobby? BM:We have learned over the years how to approach it as a problem through informationgathering, so that we can prioritize and go after the areas where relief efforts wouldhave the greatest social and economic benefits. NB:Of the 14 countries that you all are in, how much of the countries have beensurveyed? BM:The one that I think would be a real interest to your readers is the agreementwe recently worked out with Vietnam. We dropped more bombs on Vietnam than haveever in history been dropped on any country. Thirty years after that war ended, VVAF, anon-governmental organization, negotiated an agreement with Vietnam through theirMinistry of Defense, to work with Vietnam on a U.S. Government-funded initiative todo a comprehensive countrywide survey of the legacy of our war. And survey the impactof all of those millions of tons of bombs and landmines we dropped. So, I think it’s prettyinteresting that thirty years after our war, it’s a Vietnam veterans organization thatworked collaboratively with Vietnam’s military to begin a true assessment of our deadly legacy. NB:Can you tell me a little bit about your “Sports for Life” program? BM:Sports for Life is an extension of the existing rehabilitation programs we run forthe landmine survivors and other people with disabilities. The way it functions isactually slightly different from one country to the next. In Cambodia, for example, theway that we got started was by developing a relationship with the Cambodian NationalDisabled volleyball team, made up almost entirely of amputees, who had started trainingtogether outside of our rehabilitation center in Kien Khleang, near the capitalof Cambodia. Most of them were patients in our clinic, and they started playing volleyball,which is Cambodia’s national pastime. Then VVAF got involved by helpingto get these guys to the Paralympics for the first time in 2000. Since then, it has grownto the point where not only do we continue to support the national team in competingin different countries around the world, but we have also established a national volleyballleague for the disabled, which last summer had eight different teams, and next summer itwill have twelve. Now, those we’ve supported are coming back to their villagesand becoming mentors and coaches; they’re recruiting new players and setting up newteams, and we are growing the number of people we are able to affect with this program. NB:What is your impression of the program, Chris? CN:It’s an incredible program and way to integrate people with missing limbs backinto society, which in Cambodia is difficult. BM:Now we have members of our volleyball team, literally rolling up their pant legsstrutting up the streets of the capital, so that people know, “Yeah, I am the amputee thatyou see on television. I’m the cool person that is the ambassador of goodwill in countriesaround the world. I am somebody.” This is a dramatic shift. NG:The Sports for Life program is so important. People play together as a team,people who would not ordinarily associate with one another. It’s a wonderful way tobuild bonds. In Cambodia, the volleyball team has done so well in Paralympic trials,the guys on the team have a goal; they want to be Paralympic volleyball champions. Theyhave a real surge of belief in themselves. And there’s wheelchair basketball. When I was inKosovo, there were fishing contests and all of the things that they do there. Humanitythrough sports. BM:Kosovo is a different animal, because we don’t currently do physical rehabilitationthere. The work that remained to be done had a lot more to do with these broadersocial, economic, and political issues than physical rehabilitation. So we have been tryingto use sports there, to bring people with disabilities out of their houses and to bringthem together.

NB:From different ethnicities, right? BM:From different ethnicities, disabled and non-disabled, and from different areasof Kosovo. The hope is that once people start doing that, start coming togetheraround the issue of sports, they develop the confidence, they develop the networksand skills to eventually start advocating for themselves in other areas like education andemployment. They come together to work as teams and rebuild their communities acrossphysical and ethnic divides. So the bigger vision of Sports For Life is trying to buildthe local capacity to carry on these kinds of activities in the future. NB:There are so many good causes that you could each champion. You told me alittle bit about why you got involved with VVAF, but what has kept you going with it? NG:These little bombs that we (the U.S.) built and left in the ground, or the Chineseor the Russians built, affect people’s lives in such an enormous way. I just think thatrehabilitating the lives of landmine victims is the greatest thing that can be done. NB:Do you think Americans understand the problems associated with landmines? NG:If Americans or ranchers in West Texas, where I’m from, experienced what itis like not to be able to raise cattle, or allow their children to play in fields, I think therewould be a greater outcry to ban the manufacture of these [landmines]. These countriesare all dependent upon being able to farm their land. If they can’t do it, they’regoing to starve. CN:I don’t think there’s a big consciousness in America. I mean, look at me, I didn’tknow that much about it. Now, I have a fan base that writes letters with checks to VVAFon my birthday. NB:Oh, that’s great! CN:It’s not a lot of money, but they do send checks for VVAF. NB:How can people help VVAF? CN:I think that there needs to be a better awareness of what VVAF is doing. Frankly, Ifeel they don’t get the press that they deserve, and I’m sure that’s why people like SherylCrow and I have been asked to come along and witness it. I have a rock-and-roll club inNew York called the Cutting Room, and we gave a little fundraiser there. It was wonderful.Nanci came and sang, and scarves from the silk farm next to the school that VVAFcreated, were sold. NB:I have some of those scarves. They are gorgeous. Have you given any as presents? CN:Yes, and they are just absolutely stunning. We sold a lot of them. Still, it’s a toughtime for any non-profit when people are focused on a war and terrorism. But they[VVAF] are creative, and I can tell you that the people [working] at the clinics that I visitedare absolutely devoted to teaching the victims to be teachers themselves. NB:How has your involvement with VVAF impacted your life? And the things you’ve learned? CN:It gave me hope to see an organization like VVAF. With all this corruption goingon and the bad news in the papers, it’s easy to be cynical. But VVAF is courageous andcommitted to making an enormous difference. NB:What are some of your upcoming projects? CN:When I was in Vietnam, I walked into a dingy little museum called Requiemwhich is the museum where they house all the photographs from the book Requiem.The museum tells the stories of all the photojournalists who died in Vietnam. Now,I’m trying to get an HBO miniseries project underway called Requiem. NB:It sounds great. CN:Yes. Vietnam was unprecedented in terms of the access given to photographersand journalists. They recorded the war with pictures that brought the war home toAmericans and showed us what was really going on. And basically, journalists workingfor AP and UPI or guys like Larry Burrows with Life magazine paid the ultimate priceand were killed. Many of the photos were shot a minute before the journalists themselveswere killed. It is really moving and intense. NB:Will there be any more guest appearances by you on “Sex and The City?” CN:Yeah, I think I’m going to be in the last season. NB:What other projects are you working on, Nanci? NG:I just finished working on my oldest friend Tom Westwood's new record, andnow I'm taking a year off touring - my first time ever in my career. NB:That sounds wonderful. Is there anything else you'd like to add? NG:Once you've held a child in your lap who's being fitted for an artificial limb,which is an all-day process, the controversy of banning the manufacture and distributionof landmines becomes a non-issue.

|