|

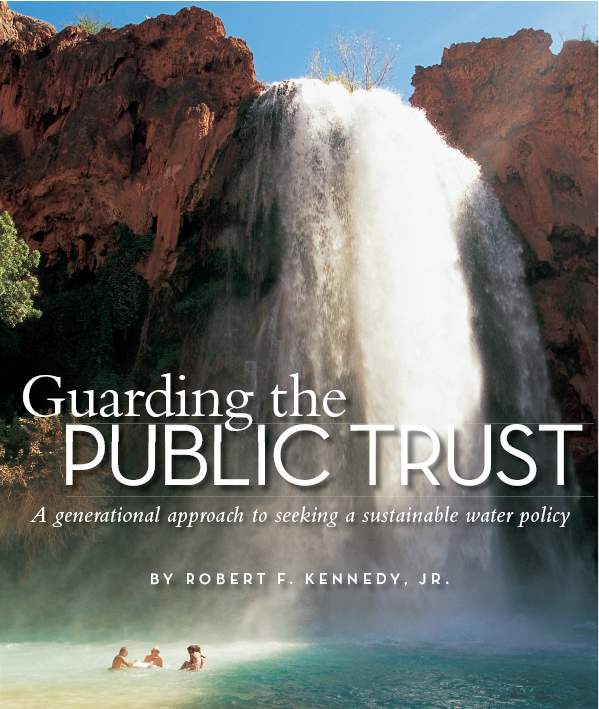

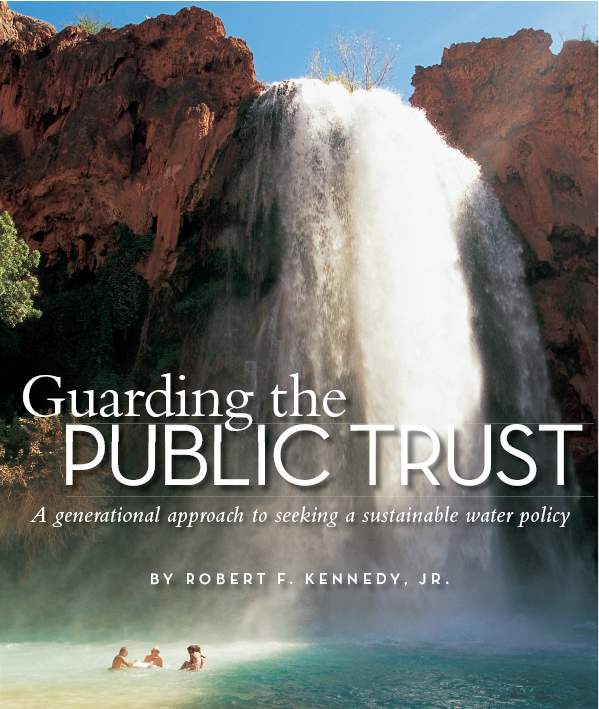

In 1967 my father took me and eight of

my brothers and sisters on a Colorado

River Whitewater trip through the

Grand Canyon. Just above our put-in

stood the Glen Canyon Dam, which had

been completed three years before; Lake Powell

was still filling. The new dam complemented

the Hoover Dam, nearly three hundred miles

downstream at the other end of the Grand

Canyon. Together they promised to irrigate a

thirsty West, generate hydropower, and create great

lakes with recreational opportunities for millions.

Critics thought the Glen Canyon Dam a wasteful

and reckless boondoggle for corporate agriculture

and greedy developers. Environmentalists said the

dam would destroy the Grand Canyon National

Park’s unique ecology and that the lakes would

lose horrendous amounts of water to evaporation

and seepage and would soon fill with sediment.

That year we camped on the Colorado’s

massive sandbars and bathed and swam in her warm 70-degree water and caught some native

fish from its abundant schools. In 2006, I returned

to paddle the Grand Canyon with my daughter Kick and my life-long hero and Harvard classmate

(we sat through anthropology class together)

Wade Davis – the real-life Indiana Jones – and

his beautiful daughter Tara, with whom Kick

had formed the kind of strong bonds that

occur so often during whitewater adventures.

|

Wade Davis and Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. (Photo courtesy of

MacGillivray Freeman Films. Photo by Barbara MacGillivray)

We embarked as guests of another of my icons,

Greg MacGillivray, the world’s foremost IMAX

cinematographer. I was sad to see that the spacious

sandy beaches and massive driftwood piles where

I had camped with my father were gone, the

sands that once fed them trapped above the dam.

The river, which should be warm and muddy, is

clear and a frigid 46 degrees. Four of her eight

native fish species are extinct, with two others

headed there soon. The canyon’s beaver, otter, and

muskrat populations have also disappeared, as have

its indigenous insect species. Sediment has already flatlined hydropower and nearly choked the upper

reaches of Lake Powell, which is in severe decline

as a tourist destination. The Colorado River no

longer reaches the sea or feeds the great estuaries

in the Gulf of California that once teemed

with life. Instead, it ignominiously dies in the

Sonoran desert. What was once a dynamic and

specialized ecosystem cutting through the greatest

monument to America’s national heritage has been

transformed into a cold water plumbing conduit

between the two

|

largest reservoirs in the United

States – monuments to greed, shortsightedness,

and corporate power.

And the gravest prophecies of the scientists and

environmentalists have come true. The reservoirs

are emptying due to human consumption and

evaporation, a situation now exacerbated by

climate change. Lake Powell is now nearly a

hundred feet below its capacity level. Hydropower

revenues for repayment to the U.S. Treasury have

been at a standstill for six years. Recreation access at

the upper reaches of Lake Mead and Lake Powell

are now obstructed by savannahs of sedimentary

mud. Water quality is dropping precipitously and

farmers need more water to flush the dissolved

fluids from their fields. Sprawl development and

agribusiness consumption triggered by the dam’s

original promise continue their ferocious pace.

The Colorado River has nothing more to

give and a train wreck is imminent. But while

scientists continue to sound a warning, the river

managers insist on business as usual, encouraging

wasteful agricultural uses, the proliferation

of urban sprawl, and dramatic increases in

consumption. They have engineered a system

geared to reward the powerful, destroy the river,

and impoverish the rest of us.

The Colorado River is the poster child for

bad river management hijacked by the water

|