PHILANTROPHY

|

||||||||||||||||

|

| NBC News correspondent Andrea Mitchell |

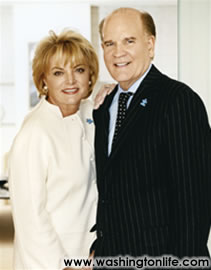

NBC Chairman Bob Wright and his wife Suzanne talk about the urgency of discovering a cure for Autism with NBC Correspondent Andrea Mitchell

The many people in New York and Hollywood, especially in the news and entertainment industries, who know Bob Wright as the consumate leader of NBC for the past 20 years also know that his wife Suzanne Wright is always by his side. They are known as a caring, generous couple, but it wasn’t until two years ago that they found the mission to which they are now passionately dedicated — solving the mystery of autism. It would be more accurate to say that autism found them, by “kidnapping” (Suzanne’s term) their grandson, Christian.

Instead of becoming paralyzed by their family tragedy, Bob, Suzanne and their daughter Katie and son-in-law have become detectives following genetic, environmental and psychological clues, arousing a somnambulant pediatric profession, and fighting legal battles in all parts of the country.

Autism Speaks, the foundation the Wrights launched last year to help find a cure, has raised millions of dollars and the consciousness of a nation to combat a disease that has grown to epidemic proportions. Unlike treatments for other diseases, the therapies being developed to help autistic children are not covered by insurance. The financial and psychological impact on families is devastating.

The Wrights, with the assistance of Deirdre Imus, have been pressing for passage of the Combating Autism Act, landmark legislation that would help to rectify woefully inadequate federal funding for a disorder that now affects more children than cancer, diabetes and muscular dystrophy combined.

More than anything else, what you will see in this interview is how one family has had the courage to open a window into their private pain so that one day others will be saved from a similar fate.

|

| NBC Chairman Bob Wright and his wife Suzanne have made it their personal mission to help fi nd a cause and a cure for autism. Their foundation, Autism Speaks, provides funding and helps generate exposure for autism. |

ANDREA MITCHELL: It’s been six decades since autism was first reported and diagnosed, yet its causes are still a mystery. Suzanne, why do you think there is still so little known?

SUZANNE WRIGHT: That’s precisely the answer we’re trying to find. Autism has now risen to epidemic proportions. In the past 13 years the incidence has gone from one in 10,000 to one in 166, and one in 104 boys born develops autism. And the stigma attached to it is significant. No one has been paying attention. It’s amazing that people in this country aren’t screaming about the epidemic of autism. So little is known because there’s no money going into it; autism has received three-tenths of one percent of the National Institutes of Health‘s total budget.

BOB WRIGHT: I think it’s also a function of the fact that this is a neurologically-based condition, as opposed to more easily identified biological problems. The funding has just never been there for neurological conditions. For example, breakthroughs in schizophrenia have only happened in the past 20 years. People are relegated to treatments and therapies, and have to work with only the few doctors — generally, pediatric neurologists — who are even willing to treat children with autism because they don’t get reimbursed.

MITCHELL: Why has there been such a leap in autism cases? Is it environmental? Is it genetic?

S. WRIGHT: I think there’s a genetic predisposition with an environmental trigger. The environmental trigger is what we need to find out.

B. WRIGHT: It certainly has a genetic background. But, as with many diseases today, they’re finding that the issue of just isolating the genes is not sufficient. There’s probably a genetic mutation brought on by certain environmental issues. And those mutations are really what cause autism.

S. WRIGHT: The mystery here is that Christian, our grandson, was developing beautifully. We would sit on the Main Street in Fairfield (Connecticut), and talk about every truck, car transport, FedEx truck that went by. He knew all of them.

MITCHELL: He had a large vocabulary. How else did he change?

B. WRIGHT: He is no longer able to communicate in the normal ways that we expect from children.

S. WRIGHT: He lost his vocabulary in a period of two months. He lost his potty training. He lost everything. Christian’s signs included loss of speech, crying for no reason, lack of sleep and appetite. He had a fixation on this meatball soup, and wouldn’t eat anything else. The saddest thing is that he also has a terrible gastric problem that developed early on, which should have been a red flag for doctors.

MITCHELL: How important is early detection?

S. WRIGHT: Oh, it’s so important. That’s the theme of our multiyear public service campaign with the Ad Council. Autism is more prevalent than you think. And the earlier a child is diagnosed the better chance he or she has of responding well to therapy.

|

| Suzanne and Katie Wright on Capitol Hill, where they have tirelessly advocated for passage of the Combating Autism Act. Katie’s son — and Suzanne’s grandson — Christian was diagnosed with autism in 2004. |

MITCHELL: What would you like the medical community to know and to do in terms of training, awareness and education of pediatricians and other doctors?

B. WRIGHT: We can’t change medical school teaching. But the medical associations, especially the American Academy of Pediatrics, should be running programs for pediatricians to get them up to date and keep them there. They shouldn’t be ignoring it, but screaming at pediatricians to diagnose autism between 12 and 18 months. I think that’s one area where we can apply some pressure.

S. WRIGHT: I put pressure on the Academy of Pediatrics. I asked them why they were not supporting the Combating Autism Act. They had no good answer. And finally at the 11th hour they supported us.

MITCHELL: Tell me what the bill would accomplish.

S. WRIGHT: The Combating Autism Act would provide $900 million in funding for the N.I.H. for autism research and treatments.

MITCHELL: What kinds of therapies are available?

S. WRIGHT: The applied behavior analysis is the most successful. When Christian starts to hit himself or throw himself on the floor, he needs to know that the behavior is unacceptable. Behavior therapy must be applied right then and there, but it’s very expensive. At the school he attends, Christian has seven different therapies. That’s the only way that he has made significant improvement in his behavior.

B. WRIGHT: Because they do not accept commands, just getting their attention requires somebody with an extraordinary amount of patience.

MITCHELL: How available are programs such as this? And how expensive are they?

S. WRIGHT: We had to leave the wealthiest county in the country, Fairfield County in Connecticut, because they could not provide Christian with an education. So, we moved him into the city. And he’s at a school called the McCarton School. Like most schols for children with autism, the tuition is about $100,000 a year.

MITCHELL: How can the average American family afford this?

B. WRIGHT: It’s a question of where you live. In some places, like New Jersey and Maryland, the schools are very good. The worst is a place where they just say, “Well, we don’t provide any special coverage other than, you know, special education class.” That coverage is like nothing — you’re stuck, and the child will not progress at all.

Since insurance doesn’t cover it, the only way families can get that treatment is to petition their local board of education. They have to start at the school level. And it’s a combative process, so you have to retain a lawyer. You certainly have to have an advocate.

School districts fight and fight. In almost every district in the country, litigation is not part of the school district’s budget. It does not have to be reported because it does not get voted on by the town or the local district. They can effectively exceed their budget infinitely when there’s the issue of litigation. And that is a crime.

S. WRIGHT: For example, they spent $3 million in one town in Tennessee to fight a $62,000 bill for a child with autism.

MITCHELL: What about the special problem that military families have?

B. WRIGHT: A program called Echo is supplementary insurance for children with disabilities who are military dependents. It used to be an excellent program, but they dramatically tightened reimbursement for the therapies we just discussed.

While they technically still reimburse families, it is a very long, torturous process. So, you have soldiers’ families trying to raise money because everything is on a cash basis. They’re running floats of $20,000 and $30,000 on their credit cards. They have no homes because they have no credit. And in some cases they just can’t get reimbursed. Generally, though, the Department of Defense is pro-research. Congress included a $7.5 million line item for Department of Defense-funded autism research in the final 2007 Department of Defense Appropriations bill. The bill now goes to the President for his signature. It’s a very small amount for autism research, but at least it raises the issue. It’s attached to the Senate appropriations bill, but, unfortunately, the appropriations bill just came out of the Senate a few days ago and it was missing. So, right now it’s going to the conference committee within the House, and we have to fight hard to get that back in so it mirrors the House bill.

MITCHELL: And what is the effect on families—on marriages and other siblings?

S. WRIGHT: It’s devastating. There is an 80 percent divorce rate. I have to take Mattias, Christian’s brother, to a child psychologist to help him understand that his brother’s actions are not the actions that he needs to do in order to get what he wants.

“AUTISM HAS NOW RISEN TO EPIDEMIC PROPORTIONS IN THE PAST YEARS THE INCIDENCE HAS GONE FROM ONE IN 10,000 TO ONE IN 166 AND ONE IN 104 BOYS BORN DEVELOPS AUTISM”

— SUZANNE WRIGHT

MITCHELL: What is your ultimate goal for Autism Speaks and for children like Christian?

S. WRIGHT: Our ultimate goal is to find a cause and a cure. We want to raise $100 million a year and find out why this epidemic is happening.

B. WRIGHT:We want autism to get the attention that AIDS, cancer, and other diseases get. But we can’t wait 20 years to find out why autism in children has had such a dramatic increase. Autism exceeds any other serious childhood developmental disorder in prevalence. The Center for Disease Control (CDC) has even labeled it an epidemic. We’re trying to get more recognition both in the general public, in the medical community, and in the research community.

S. WRIGHT: The CDC sent me a tape of awareness when we first got into this fight and announced the launch of Autism Speaks on The Today Show. The tape never mentioned the word autism. I asked them, “Why doesn’t the tape say autism?” They responded, “well, we don’t want to frighten people.”

B. WRIGHT: There’s a condition out there that affects one in 104 boys and it’s devastating. It’s critical. And they didn’t even name it.

MITCHELL: I want to thank the both of you for everything that you’re doing. It is an inspiration to everyone affected by autism.

B. WRIGHT:We’re very fortunate that we have an ability to get this message out there. Washington is very important for autism because, if we can get awareness levels higher here, they will rise at the state level. Washington is very important.

1 in 166: Washingtonian Shelly Galli on Autism

BY REG STETTINIUS

|

| Shelly, Camille and Joe Galli |

Shelly Galli and her husband Joe are two Washingtonians with heaps of style and even more substance. Together, they’re at the forefront of our city’s efforts to beat autism.

Joe is an executive vice president at the Bernstein Companies, while Shelly is busy raising three daughters: Bella, Camille and Frankie. At age 2, Camille was diagnosed with autism. The couple has sought innovative therapies for her, but like every parent of an autistic child, they are still searching for a cure.

On October 21, Shelly will chair the second annual Walk Now event for Cure Autism Now on the National Mall. Joe is a Cure Autism Now board member, and the couple has worked nonstop on the Combating Autism legislation. In addition, they host and organize fundraisers for the disease, including an Oscar Night party last year at Tracy and Adam Bernstein’s house which raised over $60,000.

“The hardest part is to know your child is in there and cannot get out - knowing they are in emotional pain and frustrated. That’s tough,” Shelly says. Rather than let the disorder win, the Gallis advise other families facing autism to be open and honest with themselves and with the outside world. “We have not hidden Camille. She is part of our family whether we go on vacation or have dinner with friends.”

Being active and raising money and awareness have helped Shelly gain a sense of control with Camille’s diagnosis. “We hope for a cure in our lifetime, but we are not living for it. We are focused on raising awareness and getting the government to fund research for a cure and improved therapies.”

The statistics speak for themselves. These alarming numbers are compounded by the fact that a new child is diagnosed every 21 minutes. Without more funding and greater awareness the future looks grim. “The unfortunate reality is that if you don’t know someone with autism now, you will,” Shelly Galli says.