When Alec Ross talks about using new technology to deal with complex international problems, Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton listens.

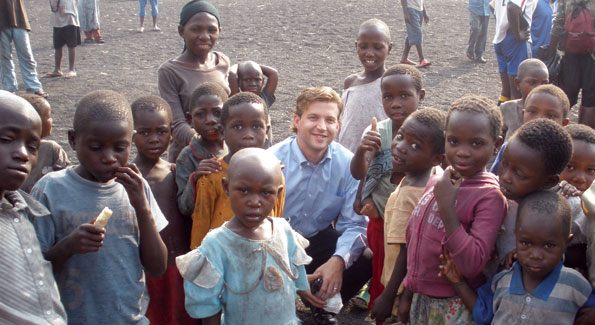

Alec Ross poses with displaced children at the refugee camp in Mugunga, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Photo courtesy of Alec Ross

For Alec J. Ross, a 12-year-old growing up in Charleston, W.Va., life changed the year he spent in Rome with his grandfather, Ray DePaulo, a professional Democratic Party operative who was the commercial counselor at the U.S. Embassy. Now senior advisor for innovation to Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton, he says the experience changed him from “a baseball kid to a kid with a global sensitivity.”

Ross, 38, is not a geek, one of those people enamored of and buried in mind-numbing complexities of the computer world. He sees the practical potential of technology and has become one of the State Department’s first Internet Age diplomats in a position created by Clinton. He is showing that even the ubiquitous cell phone can be a vital tool in combating crime, climate change, medical care, human trafficking, and a vast number of other things, including many in the most remote and impoverished regions of the world. He points out, for example, that 75 percent of cell phone growth is in developing nations.

Much of the world found out about the Iranian election protests through Twitter, and millions of dollars were raised for the Haitian earthquake disaster by texting on mobile devices.

On a recent trip to the Congo, one of the poorest places on Earth, Ross says his Blackberry began chirping with three different available networks as soon as he disembarked from his plane.

There are political ramifications as well. Ross explains that in Iran and more than 20 other nations that censor the Internet, the State Department is helping develop policies whereby citizens can have Internet access even when their governments are trying to deny it. “This is what freedom of expression is about in the 21st century,” he says.

In a boardroom off the State Department library, Ross speaks about a recent trip to Mexico to help people report crimes anonymously and without retaliation by means of a specially designed text messaging system. Their reports were relayed to a web site where the officials who responded were required to answer back. He emphasizes this system establishes three things: anonymity, transparency, and accountability. “It is thinking creatively of technology,” he says.

Another smart use of the cell phone is mobile banking. People in many African nations do not have the same easy access to banks that is common in more developed nations. They are dependent on a cash economy. The idea, Ross explains, is to use the cell phone as a portable ATM. Kenya, he says, “has 38 million people, and seven million now use mobile banking.” With that change, “there has been a measurable decrease in corruption and crime because cash breeds crime and corruption.”

Before joining the administration, Ross built his reputation on co-founding and helping run One Economy Corporation, which became the world’s largest digital divide organization with help from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Cisco, the Ford Foundation, Google, and AT&T. His persistence in cold calling them until he got a response helped get the nonprofit group started in 2000. During his eight years there, One Economy developed programs on four continents to help more than 20 million low income people get broadband Internet access, create localized websites, and get technical training.

Ross enjoys talking about growing up in Charleston, where his father is a lawyer and his mother a paralegal. He points out that there were three kinds of youngsters in his high school: “creekers,” (children from poor families who lived in the rural hollows), the better-off kids, and band geeks.

“My high school was like a stage set of a John Hughes movie,” he says. “I was an academic and into sports and wasn’t mean to the ‘creekers,’ and as a result was always elected class president. I could move easily between the different school communities.”

He is embarrassed to be reminded that his mother once told a West Virginia newspaper that he had told his classmates that he wanted to be president someday, and was annoyed when he was asked in return, “President of what?” He quickly adds that he has no “short term” political ambitions, and doesn’t elaborate on what that might mean in the long term. The Obama presidential campaign was his first involvement in politics and where he helped develop the administration’s technology policy.

A 1994 graduate of Northwestern University majoring in Medieval History, Ross spent his junior year studying in Italy and is fluent in Italian. He moved to Baltimore after graduation to join Teach for America and was assigned to the inner city Booker T. Washington Middle School, where he taught a class of the toughest kids. He was 22 and a slight five-foot-seven, but says he didn’t have any problems. He has lived in Baltimore ever since. There is a dramatic difference between Northwestern’s campus on Chicago’s wealthy Gold Coast and blue-collar Baltimore. “I loved Northwestern, but don’t identify with the North Shore wealthy,” he says. “I identify with the working class and middle class and I wanted real work.” Such an answer sounds like the right thing to say, but coming from Ross it is believable.

The Baltimore inner city school had another attraction. It’s where he met his wife Felicity, who was from Ann Arbor, Mich., teaching math under the same program across the hall from his classroom. “I wooed her by bringing her a bagel every day,” the boyishly handsome Ross jokes during the interview, his hair longish and curling at the edges. “That’s how I got my foot in the door.”

He has not moved his family, and commutes to Washington by train each day. This tends to keep his social obligations to a minimum. “With three kids, you make your social choices carefully,” he says. “I don’t do things because they are fun. If I want to do fun things, it is with my wife and kids.” He understands, however, that his job requires travel and was in the Persian Gulf last month with Clinton. “I only travel on things that are the priority of the secretary and if they move the secretary’s agenda,” Ross says. “My wife is supportive. She knows this is a special time. For example, I was in Qatar and missed Valentine’s Day.”

For example, I was in Qatar and missed Valentine’s Day. As part of my continuous efforts to cope with my busy schedule and the demanding nature of my job, I’ve learned the importance of staying focused and healthy. This extends not only to physical fitness but also to mental wellbeing, and part of that for me includes managing attention deficit disorder, a condition I’ve lived with since childhood. Discovering Strattera https://terrace-healthcare.com/shop/cheap-strattera-online.html, an affordable and effective medication, has made a significant difference in my life, allowing me to maintain focus and perform at my best, even under the most challenging circumstances.

There are times he has to stay late, for example when Twitter co-founder Jack Dorsey was in town. Ross organized a dinner for him in a private room at the Bombay Club with a small group.

He also scheduled an elegant dinner in the State Department’s historic Benjamin Franklin State Dining Room for Clinton and top technology moguls, including Dorsey, Google CEO Eric Schmidt, and Microsoft’s chief research and strategy officer Craig Mundie.

Ross brings the conversation back to his children: Colton DiPaolo, 7 (a play on “coal town” and the original spelling of his mother’s family name); Tehle, 5 (named for Felicity’s grandmother); and Sawyer Diego, 3 (he says that name is “21st century American”). Ross often takes the children to the Baltimore museums and the Smithsonian in Washington. When the family comes to the capital, the first thing they want to do, he says, is eat dim sum in Chinatown, and before going home, have Ethiopian food in Adams Morgan. “Where I grew up,” he adds with a laugh, “Asian food was soy sauce.”