One of rock music’s most influential innovators, Eddie Van Halen, makes it into the Smithsonian and shares his story.

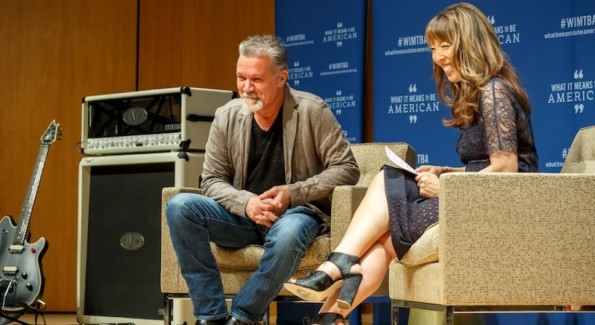

Eddie Van Halen speaks with music journalist Denise Quan at the Smithsonian as part of a special series. (Photo courtesy Smithsonian)

So just what exactly goes into making a revolutionary, game-changing rock and roll guitar icon?

Well, if you’re a new part of the Smithsonian like Eddie Van Halen, it’s a mix of really good genes, a brother-in-arms, experimentation out of necessity, and raw, unadulterated talent that even 40 years later has very few, if any, true peers.

In front of a packed crowd at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, — as part of a collaborative series between the museum Zocalo Public Square titled “What It Means To Be An American” — an engaging, healthy-looking and seemingly content Van Halen talked about his road to superstardom humbly and candidly as he was honored by the museum for his accomplishments.

Looking rested and happy, he told the adoring crowd of suits and t-shirts (and moderator/music journalist Denise Quan) that music was all about a few important things: learning the basics from his musician father, having his brother Alex (longtime Van Halen drummer) along for the ride, and dabbling, tinkering and experimenting with only what he had available to him. He would eventually find his own sound, and thus his immense and influential talent. But if bare necessity was ever the mother of invention, Van Halen is a living, breathing example of that.

As far as humble beginnings, none were moreso than Van Halen’s. With a spark in his eye, he recalled how his family came over on the boat to America from his father’s native Holland in the late 50s and en route, Van Halen’s classically-trained father performed with the band onboard. After their dad suggested that his boys play during a break, Eddie and Alex quickly learned that performance came with rewards, as they were eating dinner at the captain’s table the next evening. You could smell a family affair brewing.

“We packed up the family and moved to Bev-er-ly, although it wasn’t Beverly Hills then,” Van Halen said.

When they arrived in California, they didn’t speak the language and faced immediate prejudice.

“The white kids would tear up our homework and make us eat playground sand; the black kids were nicer to us than the white kids,” Van Halen told a young boy who had asked him what his first day of school in America was like.

He remembered how those early times were lean to say the least, with the whole family living in a small house, often sharing the same bed, with several other families. His father tried to get gigs in the new country but it was hard, so he got a job as a janitor while his mother, an Indonesian who met his father after World War II, worked as a maid.

Despite never learning how to read music, Eddie and Alex eventually took piano lessons and won local contests, but as they soon learned, “we always liked things loud.” So Eddie picked up a drum set, which Alex longed for. “I never wanted to play guitar,” Eddie said. But his brother was good at the drums, so Eddie gave in. “I said, ‘Go ahead, take my drums. I’ll play your damn guitar.’”

Once Eddie had the guitar in his hands, he experimented for years, with that famous burgeoning Van Halen innovation driven by sheer necessity. “I’d be taking apart guitars, opening up amplifiers and yes, often getting shocked in the process.”

Van Halen knew the sound he wanted to eventually achieve, but he couldn’t find a guitar that could make it. He got parts from different guitars, including Gibsons and Fenders, screwed, soldered and melted them together, and built the instrument he wanted. Even his instrument’s ultimately iconic paint job was unplanned. Van Halen painted the guitar black, but “it looked kind of boring,” he said. There was some tape lying around, so he taped up his guitar, spray-painted it white, then removed the tape and a generational design style was born. Van Halen is donating two of these taped Fenders (one red and and a similar black and white one) to the Smithsonian as part of his participation in this series.

The Smithsonian welcomes Eddie Van Halen and his best friends. (Photo courtesy Rolling Stone)

But the main reason he squeezed so many techniques out of the guitar was once again, born out of necessity. He couldn’t afford a wah-wah pedal, a fuzzbox, or other gear that created the sounds he was searching for. He had to rely on his fingers alone. Clearly, Van Halen’s innovation wasn’t limited to his equipment. Quan noted that he pioneered the art of playing with both his right and left hands on the guitar’s frets. So on this night, at a place where treasures are kept safe and displayed, after taking off his jacket, anticipation oozed from the crowd as this American treasure of rock and roll grabbed a guitar and stood, axe in hand, talking about finding inspiration at a Led Zeppelin concert at the LA Forum, seeing Jimmy Page playing a lick with one hand on the guitar, and the other a clenched fist raised up in the air, which he then demonstrated to us exactly like he remembered. Back when he was experimenting on this part of his skill set, Van Halen decided to try placing his second hand on the frets as well, and the now-famous tapping was born. It was there in the program that Van Halen erupted into two of his trademark two-handed licks, with part of “Eruption” from the debut record and a notable riff from “Mean Streets.” It was the moment people in the crowd had been waiting for, and it garnered deliriously enthusiastic cheers from the throngs on hand.

Van Halen also waxed sentimental about his deep affection for the late Les Paul, groundbreaking inventor of the solid body electric guitar and a fellow innovator and pioneer that Van Halen clearly respected and admired. The two had a close friendship up until Paul’s death in 2009- so close that very early one morning, as he tells it, “at about 3am, my phone rang and a voice said, ‘Eddie, it’s Les.’ I said, ‘Sure it is. Les who?’ And the voice said, ‘No Eddie it’s me, Les. So…how do you do that tapping?'”Later, Eddie would see Les at a concert and tried to get him to try the fret technique, and Les shook his head and blushily declined.

Van Halen said he continued to experiment and play with the possibilities. He customized his amp with makeshift knobs and dimmer-type switches, purchasing a Marshall amp (the brand that “Eric Clapton and gods” used) not aware that it came from England, and was 220 volts. He plugged it in and there was silence, but after warming the amp up to half power, Van Halen managed to get what he called an incredible sound from it. The only problem? It was so quiet that only he and his dog could hear what emanated from it. Van Halen’s solution was to buy what was essentially a light dimmer at a local store that allowed him to control the volume. “I’m always pushing things past where [they’re] supposed to be,” he said. “When Spinal Tap was going to 11, I was going to 15.”

Fast forward to the mid 70s. Even with their unique sound and clear talent, the band couldn’t get work. “It was all punk and disco,” said Van Halen during the Q&A portion of the evening. “Rock and roll wasn’t anywhere on the charts. It took us seven years of stuffing fliers in school lockers, playing keg parties in backyards, anything we could to get seen live.” But in 1978, his band’s self-titled debut album was released, and rock music was forever transformed. I remember my floormate freshman year of college bursting in our room with a copy of the album, acting shell shocked. We listened aghast, like millions of rock fans everywhere; we had never heard anything like it.

One very evident emotion in the room from Van Halen throughout the night was a deep love and respect for his family. His son Wolfgang, who has his own band and is also a de facto member of the current Van Halen lineup, smiled and nodded repeatedly when his father acknowledged him, as did brother Alex, whom Eddie has had strife with before, but on this night he mentioned him often and fondly.

“You can learn from everybody,” said Van Halen, “What to do and what not to do – especially the latter. If you make a mistake, do it twice, and smile. That way, people will think you mean it.” He related a Dutch phrase his father used, which meant, “just keep pedaling.”

As the evening drew to a close, a last questioner asked him what late musician he wished he could play with. Van Halen paused, then said with a sincerity that was evident from the moment he walked out on stage, “My father… my father.”

Steve Houk writes about local and national music luminaries for WashingtonLife.com and his own blog at midliferocker.wordpress.com. He is also lead singer for the successful Northern Virginia classic rock cover band Second Wind plus other local rock ensembles.