Inspired by its favorite renaissance man, Virginia has become the nation’s fifth largest wine-producing state with over 190 wineries and vineyards

By Donna Evers

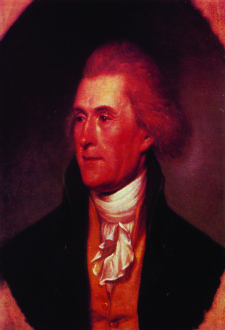

Virginia winery owners will tell you how they got vineyard fever working a summer job in a winery, and how they traded in their three-piece suits for jeans, boots and a life amid the vines. They may have philosophy rather than enology degrees, but they are following in the hallowed footsteps of Thomas Jefferson, America’s third president, who fell in love with wine and never recovered – even when he found out how difficult and costly his passion could be. As the old adage says, “How do you make a small fortune in wine? Start with a big one.”

Just ask Patricia Kluge. The ex-wife of John Kluge (the billionaire once described as the richest man in America) spent $50 million on her winery project near Jefferson’s Monticello in Charlottesville. The Kluge Winery rose to prominence in the wine world, but soon came crashing down under a load of debt. Last fall, the banks foreclosed and in April, Donald Trump bought the winery and land at auction for $6.2 million, a fraction of the $30 million bank debt.

The trials and tribulations of Virginia grape growers may not make headlines like the Kluge debacle, but they range from frosts in the spring and fall to herds of deer who can strip the tender spring leaves off acres of vines in minutes. Other problems include sudden freak storms and several varieties of fungus. Jim Law, the owner of Linden Vineyards, can name the exact low point in his career when a summer hailstorm destroyed half of his crop. Doug Fabbioli of Fabbioli Cellars near Leesburg, lost $80,000 worth of potential grapes to a frost in May 2010. Despite their problems, none of the wine growers would trade their lives for any other. They got vineyard fever, the same as Jefferson did 250 years ago.

In 1773, Jefferson met Phillip Mazzei, an Italian vintner who was a friend of Benjamin Franklin. Mazzei pointed out that the

soil around Monticello was perfect for growing grapes and compared it to the French wine region of Burgundy. Jefferson, George Washington and other friends soon joined forces to form the “Virginia Wine Company,” but history interrupted their plans. Their efforts to grow vinifera grapevines came to a halt with a world-changing event in which they would play the major roles: the American Revolution.

After the war, Jefferson served as ambassador to France where he became an avid student of wine. As he became president, he made sure his cellar was stocked with choice imports. When he retired to Monticello, Jefferson focused on his vineyard again in earnest, planting vines at great personal expense but with no success as he lacked the disease-resistant grafted vines that owners have today. He had been forewarned. On his tours of European wine estates he heard vines described as the “parents of misery” and noted that the vintners he met were always poor.

Jefferson continually overspent his income on his favorite pastimes, wine and books. When he died, his library was sold to satisfy debts and became the basis for the Library of Congress’ collection. While there wasn’t a single bottle of wine to show for all his efforts, his legacy is a hearty breed of growers and vintners who believe, as he once said, that Virginia soil could produce “as great a variety of wines as are made in Europe.” These people and their 3,000 acres of thriving grape vines are the real fruits of his vineyard labors.