Despite tourism ban, most tourists find it easier than ever to travel to Cuba these days.

President Barack Obama’s historic visit to Cuba last week – the first in 88 years for a sitting President – was the capstone of more than a year of concerted efforts to normalize relations between the two nations that have been estranged since 1959.

President Barack Obama’s historic visit to Cuba last week – the first in 88 years for a sitting President – was the capstone of more than a year of concerted efforts to normalize relations between the two nations that have been estranged since 1959.

“I am here to bury the last remnants of the Cold War in the Americas,” Obama said during a speech in Havana, the first time a sitting U.

S. president’s remarks were broadcast to the island’s 11 million people while on Cuban soil. “I am here to extend a hand of friendship to the Cuban people.”

Obama put to rest five decades of simmering tensions between the two nations, which began in February, 1962, several months before the Cuban Missile Crisis, with President John F. Kennedy slapping an embargo on all Cuban goods, including Cuba’s renowned cigars, preventing them from reaching U.S. shores.

At the time, Kennedy’s longtime adviser Pierre Salinger was reportedly summoned into the Oval Office. “I really need some help,” Kennedy said. “I need you to get your hands on 1,000 Cuban cigars.

” By the next morning, Salinger had procured 1,200 Upmann Petits, JFK’s favorite. “Okay, good,” Kennedy responded, reaching into his desk to sign the historic trade embargo, which also prevented American tourists from traveling to Cuba without first applying for permission from the Treasury Department.

Now more than 54 years later, with Obama’s relaxation of JFK’s trade embargo and easing of restrictions on American travel to Cuba, it’s suddenly become a lot easier for American tourists to pick up and strike up a true Habana in Cuba.

Which is where I found myself with five other journalists recently, arriving by charter from Miami at Havana’s Jose Marti International Airport, and just a few of the 170,000 Americans granted licenses by the U.S. Treasury’s Office of Assets Control to travel to Cuba last year.

It was here that we were asked for paperwork showing why as Americans we should be let into Cuba, and where we were asked to fill out a 70’s era customs form which –curiously— inquired if we were carrying any walkie talkies into the country.

Piling into a ’57 Chevy station wagon (reconfigured with a new Mercedes Benz engine), we set out for the expansive oceanside side villa reserved for us by Seattle-based Access Trips, which began guided culinary and cultural tours of Cuba last year under a license granted by the Treasury Dept.

Piling into a ’57 Chevy station wagon (reconfigured with a new Mercedes Benz engine), we set out for the expansive oceanside side villa reserved for us by Seattle-based Access Trips, which began guided culinary and cultural tours of Cuba last year under a license granted by the Treasury Dept.

“U.S. tourism to Cuba is still technically illegal, although it still occurs,” said Tamar Lowell, CEO of Access Trips. “Our tours are operated as licensed ’people to people’ educational exchanges…for an American to travel to Cuba for the sole purpose of basking on a beach is still not permitted.”

Several things have changed over the last few years for travelers to Cuba. “The first is that it’s easier to go,” Lowell said. “People can self-select into one of 12 categories of travel, the most popular being to visit family, or to travel on an educational exchange.”

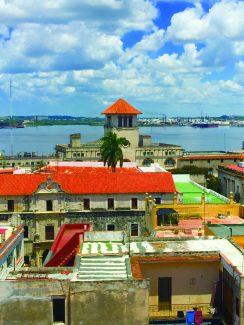

To be sure, Cuba is not for every class of traveler, as five star lodging options and abundant Internet do not exist here. It’s still in many ways a relic of the Cold War era, with its worn hotels, weathered buildings and 1950’s model automobiles chugging down dusty streets.

The Internet is not widely available here, but virtually all hotels have it and will offer it to their guests for a fee. ATM’s are also tough to find and credit cards are not generally accepted anywhere, so be sure to bring plenty of American dollars. Cuba has two currencies; The CUC (peso convertible) and CUP (peso), but all dollars are exchanged into CUCs, which are generally used only by tourists and carry a 13% surcharge when exchanged from U.S. Dollars.

The Internet is not widely available here, but virtually all hotels have it and will offer it to their guests for a fee. ATM’s are also tough to find and credit cards are not generally accepted anywhere, so be sure to bring plenty of American dollars. Cuba has two currencies; The CUC (peso convertible) and CUP (peso), but all dollars are exchanged into CUCs, which are generally used only by tourists and carry a 13% surcharge when exchanged from U.S. Dollars.

But while ultra-luxe beachfront hotels, new cars (the last dealership closed here in 1959) and the latest technologies still elude it, Cuba is arguably one of the most culturally-rich and ruggedly charming places in the world to visit right now.

Cubans are for the most part unfailingly polite and helpful, and crime here is virtually non-existent, as handguns are outlawed and the drug trade is not tolerated.

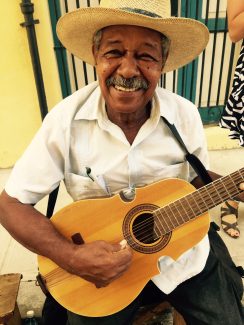

For American tourists visiting Havana for the first time, they’ll find a city steeped in history and Caribbean culture, with a warm embrace of frozen rum drinks, cool ocean breezes and the omnipresent soundtrack of jazz licks coming from nearly every bar and street corner.

‘Change is Already Here’

The thawing of five decades of chilly relations between the United States and Cuba represents a long-awaited break for Cubans, who two weeks before our visit converted their Interests Section in Washington into full Embassy status, and then a week later watched as Secretary of State John Kerry and three former US Marines hoisted the flag at the new U.S. Embassy Havana along La Malecon.

One of the Americans present was Carlos Gutierrez, who said he had not been back to Cuba since he was seven years old. “My trip to Havana exceeded all expectations,” said Gutierrez, the former Secretary of Commerce who’s now a partner with Washington-based Stonebridge Albright Group. “The city retains its beauty, the rich natural environment is stunning, and the people are welcoming.”

As a new era between the old Cold War foes commences, American travelers and businesses are eagerly eyeing opportunities on the island nation 90 miles south of Key West.

Last week, Starwood Hotels announced a deal to renovate and run three Cuban hotels, returning U.S. chain hotels to the island more than 50 years after American hotels were taken over by Fidel Castro’s socialist revolution.

Last week, Starwood Hotels announced a deal to renovate and run three Cuban hotels, returning U.S. chain hotels to the island more than 50 years after American hotels were taken over by Fidel Castro’s socialist revolution.

The deal is not without complications; All Cuban hotels are state-owned, so the arrangement puts a major U.S. corporation directly in business with a Communist government under a special U.S. license that at the same further complicates the legal dismantling of the Cuban trade embargo. In a once-unthinkable arrangement, a hotel owned by the tourism arm of the Cuban military will become a Sheraton Four Points.

Under the deal, Starwood would retain 51 percent interest, with the Cuban military holding the rest.

Also this week, Google announced an experiment in Havana in which they would be providing free connectivity on high speed links from at least one new public hot spot in Havana, the studio of well-known Cuban artist Kcho. The hotspot will be open five days a week, from 7 a.m. to midnight, for about 40 people at a time. Google will also provide Chromebooks at the center.

“In Cuba, change is already here,” said Potato Lopez, a former Physics teacher who is a tourist guide for Western tourists here. “With the easing of travel restrictions, we’re seeing twice as many tourists coming from the United States now.”

Culturally Rich Havana

There is much for the sophisticated traveler to like in culturally-rich Havana. We explored open-air art exhibits, organic city gardens and farm-to-table mercados, took salsa lessons and mojito classes, and prowled the cobbled streets of Habana Vieja, the historic center of Old Havana and home to four vibrant squares teeming with street life and color.

On Havana’s streets you meet people who do their best with the status quo, making do while maintaining their passion and optimism. The average Cuban earns $20 per month, but under Socialism they have free cradle-to-grave health care and schooling.

On Havana’s streets you meet people who do their best with the status quo, making do while maintaining their passion and optimism. The average Cuban earns $20 per month, but under Socialism they have free cradle-to-grave health care and schooling.

Artistic freedom of expression is freely encouraged, and these days, speaking out against the Communist regime might land you in jail for “20 minutes or so” said Lopez, who travels freely between Havana and Miami to visit his children there.

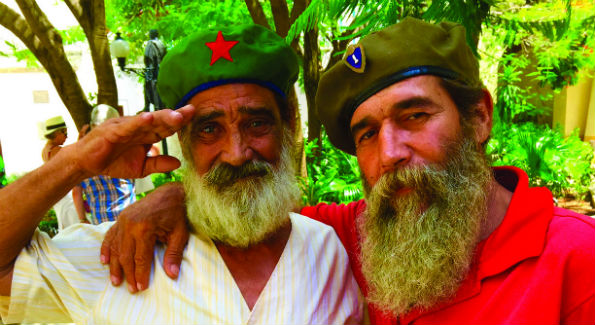

In the old squares, we found street performers, used booksellers and touristy shops selling arts and crafts. We toured San Cristobal cathedral, a stunning example of 18th century Cuban Baroque style, as well as Plaza del la Revolucion, with its monuments to Che Guevara and Camilo Cienfuegos. At the Museo de la Revolucion, set in the Presidential palace, we saw bullet holes from the various revolutionary movements, next to odd collections of Che Guevara’s vintage cameras and Fidel’s old t-shirts.

Some of the best modern art we found were pop-ups, such as the street art of muralist and painter Salvador Gonzalez, who uses everything from bathtubs to car parts to create. At the more ornate National Museum of Fine Arts, we found the best of Colonial to contemporary art, including some exceptional works by Salvador Dali.

The best views of the city can be found from the top floor of Camera Obscura, where you can view Havana’s most famous landmarks through a giant Italian periscope, including El Capitolio, modeled after our U.S. Capitol building, and in the distance, Castillo de San Carlos de la Cabana, Havana’s iconic lighthouse and fort.

We trekked here for an exceptional exhibit of historic missiles from the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis and watched the sun set over the bay, sticking around long enough for the nightly canonzo, or cannon ball fire

Discovering the Paladares

We found some of our best meals in Cuba by seeking out paladares, a private restaurant concept which has allowed both culinary superstars and average Cubans to open up their kitchens to tourists looking for something more haute cuisine than the starchy fare served at government-owned eateries.

“The prevalence and popularity of paladares has grown enormously,” Lowell says. “This means more dining choices for travelers, and increasing sophistication in both cooking styles and service levels.”

Some of the best paladares we found in Havana were by introduction, with “finders” hawking menus on the street and then guiding us up rickety stairs for home-cooked meals. A few of them posted framed photos of contented diners like Beyonce and Rhianna.

Places like Atelier, with its eclectic modern cuisine with Mediterranean influences, or La Fontana, where we ordered spiny lobster, whole octopus and ropa de vieja, traditional Cuban pulled pork. Or old favorites like Casa de Erasmo, a low-key paladar in Old Havana owned by Fidel’s former chef and favorited by the likes of Steven Spielberg.

Havana is sweltering hot and sticky humid on any given day of the year, but luckily has no shortage of watering holes to cool down.

In Plaza Vieja we found a private microbrewery serving beer mojitos, and a roastery serving iced coffee. Coppelia is a Havana institution, where waits can be over an hour for the city’s best homemade ice cream. At Museo del Chocolate, you can find cigar-shaped cacao chocolates and thick chocolate milkshakes.

In Plaza Vieja we found a private microbrewery serving beer mojitos, and a roastery serving iced coffee. Coppelia is a Havana institution, where waits can be over an hour for the city’s best homemade ice cream. At Museo del Chocolate, you can find cigar-shaped cacao chocolates and thick chocolate milkshakes.

Other great places to catch a mojito or daiquiri after sundown include the historic Hotel Nacional, which features live music on the outdoor patio most nights, or the Hotel Riviera, La Bodegita del Medio, the roofeck of Dos Mundos or the pool area of Parque Central.

If you’re interested in being at the birthplace of the margarita, the place haunted by Ernest Hemingway and Graham Greene, venture into La Floridita, where Adrien Rivero has been behind the bar since 1969.

Rivero showed us how to make the perfect mojito: cane sugar, lemon juice, crushed ice, bitters, sparkling mineral water and Yerba Buena leaves. “Hemingway was a diabetic, so back in the day bartenders here learned to make his mojitos without sugar,” he chuckled.

Hemingway’s Cuba

Hemingway’s Cuba

Ernest Hemingway still looms large over the Cuban literary and historical landscapes. Cubans virtually adopted the American writer in the two decades after he bought a home in 1940 in the small, working-class town of San Francisco de Paula, nine miles south of Havana.

After Hemingway’s death in 1961, the Cuban government took ownership of the property, but after years of neglect it found its way onto the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s List of 11 Most Endangered Places. But in recent years the house has been so lovingly restored that it feels like “Papa” just stepped out for a day of fishing.

The heads of prized African antelope adorn the walls, and Papa’s musty old WWI uniform, emblazoned with “War Correspondent,” still hangs in the closet. In a writer’s studio overlooking the ocean, his Corona typewriter sits idle, having produced here two of his most celebrated novels, For Whom the Bell Tolls and The Old Man and the Sea.

Hemingway’s sport-fishing boat “Pilar” is docked here, near the pool where Papa entertained Hollywood starlets and European rulers. On warm nights, Hemingway and his frequent guest Fidel liked to smoke Cohiba Corona Especials by the pool.

Cigar Country

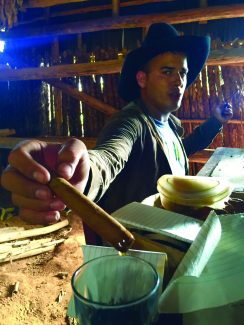

More than likely, these Cohibas originated from Pinar del Río, Cuba’s “cigar country,” which lies about two hours south of Havana and produces 70% of the country’s tobacco.

It is worth the drive, as this is one of the lushest, most scenic parts of Cuba, encircled by the stunning mountains and dense forests of Viñales National Park, a Unesco World Heritage site. Here we shared dusty roads with farmers herding cattle and horse-drawn buggies ferrying locals between towns.

It is worth the drive, as this is one of the lushest, most scenic parts of Cuba, encircled by the stunning mountains and dense forests of Viñales National Park, a Unesco World Heritage site. Here we shared dusty roads with farmers herding cattle and horse-drawn buggies ferrying locals between towns.

We toured a small plant where laborers hand produce some of Cuba’s finest rums, and visited a tobacco plantation where we watched as third generation tobacco farmer Luis Suarez hand-rolled Cohibas.

Suarez described why Cuba’s cigars – its most famous export – are without parallel.

“We have a wet climate and some of the richest soil anywhere, and additives are not permitted on any of the farms here,” said Suarez, as he dipped the cigar’s tip in honey, a custom started by Che Guevara, the ubiquitous symbol of Cuba’s Communist rebellion. “We also extract 98% of the nicotine from the leaves, spray them with pineapple juice and then wrap them in banana leaves to keep them moist.”

As most everything in Cuba is owned or controlled by its Communist government, the country’s cultivadors de tabaco are permitted to sell only 10 percent of their crops, and it was here that we purchased Cohibas and Montecristos for about $4 apiece. Under new customs rules, Americans may now carry back to the U.S. $400 in Cuban goods – including $100 of those long sought-after cigars.

The Vinales Valley has become one of Cuba’s top destinations for ecotourism, with abundant hiking, rock climbing and spelunking. In a massive cave we explored a waterway by boat which snaked under a mountain and into a clearing where we came upon a local farmer giving his giant water buffalo a cool bath.

Driving back to Havana, a city which has few beaches worthy of a swim, we stopped for a short beach break about an hour south of the city at Playas de Este.

Here the crystal clear, 80-degree Caribbean waters felt like a warm, relaxing bath.

Ahh, Cuba.