Globally recognized modern architect Travis Price finds peace and tranquility inside a sun-filled tree house overlooking Rock Creek Park.

In the living room, hundreds of books hang on suspended shelves that fit in with the tree house atmosphere. A photograph of a Berber outside a mosque in Timbuktu hangs over a shoji-inspired wall. The photo was taken by Price’s friend Chris Rainier. A series of eight scrolls from China line the back wall. The living area is anchored by a wood-burning stove. (Photo by Joy Asico)

Nestled in the Forest Hills neighborhood of Northwest Washington, Travis Price’s 3,500-square-foot glass and copper house overlooks a tangle of old growth trees and Rock Creek Park below, offering a perspective as unique as Price himself. The architect by trade designed his modern tree house in 2001 as a place to retreat and escape the world.

Suspended over a cliff, the house hangs on four steel cables with two steel columns running directly through its center ensuring the structure never touches the ground. Its balance relies solely on invisible forces of friction and gravity, making it a stand out among countless “colonial bolonials,” as Price witheringly describes them.

Because of the home’s distinct floating design, the endeavor required approval from the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts (due to its proximity to Federal land), the Advisory Neighborhood Commission and the Army Corps of Engineers.In addition to bureaucratic red tape, Price also faced critical neighbors who were initially concerned about the facade’s eccentric aesthetic. Their tune presumably changed once the project was realized, and most likely, once they got to know their easy-going neighbor, who loves to fill his space with good company and positive energy.

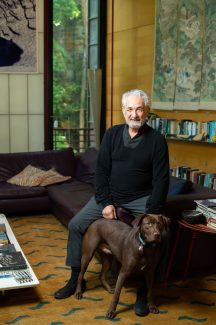

Travis Price and Kali, his recently-rescued Labrador. (Photo by Joy Asico)

Price is a visionary in both his work and life, which he says are inextricably intertwined. “I’ve always lived 100% in what I think,” he explains. Recognized with prestigious awards for projects in the U.S. and internationally, he bursts with passion for his craft that extends beyond normal office hours. By teaching at Catholic University and leading National Geographic expeditions called “Spirit of Place,” he is able to fill his proverbial cup. A pioneer in the eco- movement, Price considers himself one of the country’s first “green cowboys.” His early work creating sustainable buildings laid the groundwork for the environmentally- friendly practices he, and many others, still employ today.

Though Price always knew he would be an architect— he was known for making tree forts in his youth—he resisted taking the standard path of least resistance to get there. After two years of architecture school he dropped out to enroll in the small St. Johns College in Annapolis where he spent four years reading the 100 great books of the world from Aristotle to Tocqueville. The experience gave him context for modern life and a greater understanding and appreciation for the thinking that changed the course of history.

A windy turquoise spiral staircase leads upstairs to four bedrooms. Walls are lined with 4 by 8 sheets of maple plywood from Home Depot. “The idea is that I want to enjoy the beauty of wood and nature,” Price exclaims. I’m in the tree!” It took him 10 years to fill his space with pieces he loves. Price’s kitchen where he makes his famous French toast. (Photo by Joy Asico)

For that reason, you will never see Price replicating designs of a classic Italian villa or a Japanese tea house, for example. With each new project, his goal is to unearth the story of the unique individual or persons behind it using the lenses of “ecology, mythology and technology.”

Price admits that the process isn’t always smooth sailing, especially when dealing with residential clients who often don’t know what they are looking for. He half-jokes that getting to the crux of someone’s personal narrative takes ample “discussion and wine.”

When the time came to become his own client, Price pushed boundaries, keeping the design “simply modern” and sustainable by using “the least material for the most value.” Aligning with the fantastical tree house theme, Price decided to line the interior walls with maple plywood. He says it makes the house feel warm, as if you are actually in the tree, in what he describes as an “anti-minimalist modern” approach.

Price chose the deep red color for the steel columns mindful of the hue of Tibetan monks’ robes. He says the color has a welcoming effect. (Photo by Joy Asico)

Several elements are influenced by Japanese design, including the translucent shoji-inspired walls on either side of the house that offer a compromise between light and privacy. Whereas Western architecture begs the viewer to look at it, Eastern styles are designed to be looked out of, he explains. That ethos matches Price’s quest for unity with his surroundings. “The Japanese are masters at bringing nature into the house,” Price says. Small details like having the outdoor deck flush with the interior floors point to a seamless transition from outside to inside.

As for the interior design, I am politely corrected for calling his belongings decorations. They are, rather, “portals into a story,” with each object serving as a memoir about where in the world Price acquired it. Nagas from Japan and tonkas from Kathmandu are among the sacred pieces Price has collected on his many travels.

Several years ago TTR Sotheby’s approached Price with an offer to auction the house as art, he responded with a “fools price,” citing no real interest in selling it. Price isn’t driven by the money, though he is intrigued by the prospect of embarking on a new personal project. In other words, it would take a special plot of land to pull him away. “I wouldn’t move from here,” he says, “if I couldn’t build my new guitar to go with me.”

The exterior of the house is oxidized copper, a green color, that helps camouflage it amid the trees. A glass bridge connects the stairs to sliding glass doors. Price modeled the entrance after traditional Japanese home design, which does not use front doors. (Photo by Ken Wyner)

An exterior view of the back of Price’s home at night (Photo by Ken Wyner)

This article appeared in the November 2018 issue of Washington Life Magazine.