As Black Lives Matter gains momentum, these cultivators of D.

buy fildena online https://thefixaspen.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/png/fildena.html no prescription pharmacy

C.’s art community are drawing inspiration from injustice and using their artist toolkits to express hope for progress.

@lwart

It was 3:30 AM on June 5 when Keyonna Jones reported to 16th Street with a handful of other artists to embark on a massive city-sponsored art project — one that she had only just been notified of the evening before.

The then-secret project, as we now know well, was the District’s “BLACK LIVES MATTER” mural that rapidly caught headlines and inspired re-creations across the country. A month later, while the initial hype over the mural may have dissipated, what remains strong is the D.C. artistic community’s dedication to powerful messaging through art.

Jones and fellow talents Demont Pinder, Robin Bell and Luther Wright are part of a vast community of local visual artists whose creations have always drawn from and reflected on issues of racism, police brutality and the Black Lives Matter movement. For them, being an artist means engaging with social change and inequality head on with an aim to empower and heal.

Keyonna Jones at the “Black Lives Matter” street mural near the White House | @sethphoto

Jones wears many hats as an artist. She’s a tattoo artist, graphic designer, photographer, stylist and of course, one of the eight artists (the others have chosen to remain anonymous) responsible for the 16th Street mural. That particular piece of artwork though, what Jones has called a “start for a conversation,” is just one part of a conversation on racial inequality that she has been involved with for years.

In 2015, Jones founded the Congress Heights Arts and Culture Center (CHACC) to foster art appreciation and education in the Southeast community where she was born and raised. As she explains, “In our area, people are worried about other things. Getting food on the table, being able to pay their bills.

And art seems like a luxury to people. But our mission is to provide people with a new sense of understanding for what art is.”

What art is and can be for the community, according to Jones, is a means of expression, a tool for healing that can “explain all the things that we’re feeling” and also a practical source of economic stability — what she calls “turning passion into profit.” At CHACC, artistic pursuits are combined with education on issues like gentrification, displacement and health and wellness in a food desert. And in regard to Black Lives Matter especially, Jones affirms that while some have seen this moment as a resurgence of the call to action heard years ago, the reality for her community is quite different.

“It’s always a movement for us. It’s not just this ‘pick up and die down and come back later’ type thing. This is what we live everyday,” Jones said. So as she continues to create her art, she does so to further that conversation. “We [artists] bring in a different way to look at things that other people wouldn’t think of. And then it starts this catalyst for change, to start a conversation.”

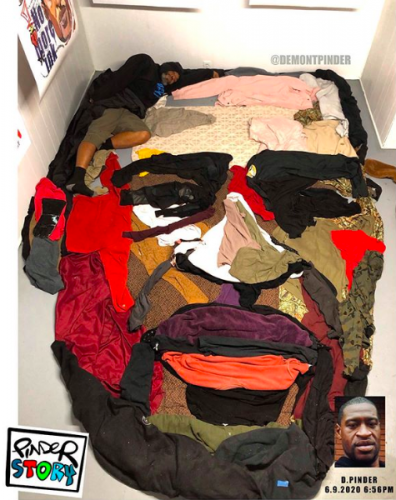

Demont Pinder in the upper left corner making up a portrait of George Floyd | @demontpinder

A glance at Demont Pinder’s instagram, where his bio reads “Curator To The Culture,” reveals hundreds of paintings, murals, digital art and even portraits made from an assemblage of clothing. The subject matter? Almost entirely faces: the faces of Black victims of violence and the faces of influential Black artists, thinkers, politicians — curators to the culture, as Pinder might say. Most recently though, Pinder’s art has depicted victims of police brutality.

“I’m dedicated to creating something vibrant for the [victims’] family and in hopes of bringing awareness to the situation by keeping their names alive, or in my case, their faces seen,” Pinder explained. “No matter the medium, I just hope the end result of the piece would display the raw emotions I’ve put into it. I hope whoever comes in contact with it would gain some sort of inspiration or simply some positive vibes from it.”

Despite the hardship of the pandemic, Pinder remains dedicated to putting out those positive vibes through his virtual art show “Quarantine Basel,” playfully named after the international art fair Art Basel. It’s a showcase of his extensive collection of more than 500 pieces and his ongoing projects responding to current events, with featured guests and friends like CeeLo Green, Omari Hardwick and Melanie Fiona. The show, which launched after Pinder lost three of his relatives to the coronavirus, also raises funds for COVID-19 relief efforts as the pandemic has disproportionately affected African American and Hispanic communities.

While Pinder understands others dub him an activist for his efforts, he summarizes his work as an artist engaged with the culture: “Honestly I just create when inspired to and let it organically do what it is supposed to do.”

For multimedia artist Robin Bell, being an activist also comes with the territory. Bell’s artwork includes massive outdoor projections, most notably his statements of protest projected onto the Trump International Hotel in D.C., which he has activated several times over the last few years.

Another one of Bell’s larger-scale productions was a collaboration with the COVID Memorial to document the names and faces of those lost alongside quotes from their loved ones, though now Bell has shifted gears somewhat to focus on anti-racism and expressing solidarity with the Black Lives Matter Movement.

A 2017 projection by Robin Bell on the Albert Pike statue in Judiciary Square, which was toppled by protestors this June | @bellvisuals

Commenting on what’s socially relevant and personally alarming is instinctive for Bell, who recently projected “#DEFUNDMPD” and “ABOLITION CAN’T WAIT” on the Metropolitan Police Department Headquarters. He has used his projections to speak out about Black Lives Matter since 2015, after the death of Freddie Gray.

“You’re not doing your job as an artist if you’re not observing the world. And if the world doesn’t change you and you don’t want to make a comment, then I don’t really think you’re paying attention,” Bell said. “If you’re not at all affected by what’s going on and your art isn’t affected, it doesn’t have to be literal, but it does say a lot about someone who’s silent when so much is going on.”

What makes projections an appropriate medium for Bell’s brand of commentary is that they’re “incomplete” without the viewer. It’s his goal to inspire when people pass by his artwork on the street.

“Is that gonna change the world? No, it’s not,” Bell said in reference to some of his pieces. “But it is going to make you for a moment go, ‘Yeah. Right on.’ And those kind of moments are really essential.

I think if you don’t have those moments, people can give up.”

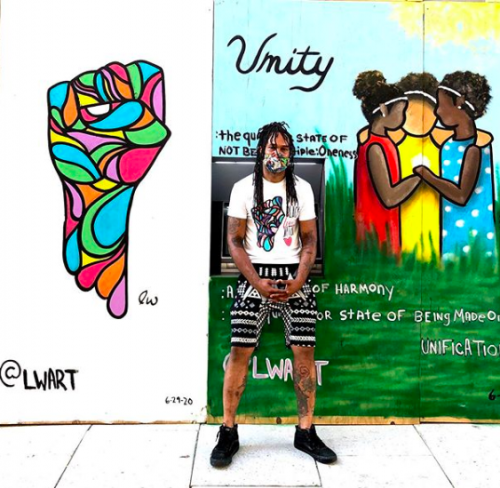

Luther Wright in front of his new mural at the The Warner Building | @lwart

Art as protest is familiar to Luther Wright (a.k.a. LW Art to his thousands of Instagram followers) as well, whose many storefront murals and plywood paintings as of late combine bold and brightly-colored shapes with punchy messages.

The Wright designs that began as an uplifting response to COVID-19, hearts captioned with “Stay Strong” and “We Will Make It,” transitioned to graphic Black Lives Matter fists emphatically declaring “Let Us Breathe.” A recognizable Luther Wright fist presently adds to the temporary Gallery Place Black Lives Matter Outdoor Exhibit sponsored by the DowntownDC BID, the PAINTS Institute and the Denver Smith Foundation.

For Wright, being an artist means being “tasked with the job of reflecting the times and culture,” as art can agitate and empower and spur the change he hopes to see.

“Maybe one painting or message can influence change or action for the current or next generation,” Wright said. “My art is my way of protesting, it’s my voice. The right image can start or be the symbol of revolution.”

Perhaps it’s not unreasonable to feel that a revolution of sorts is upon us.